How charities can avoid running out of investment money

Charity investment portfolios deliver the income and investment returns that fund long-term projects, but rising pressure is leading to unsustainable spending strategies that could cause charities to ultimately run out of money.

Two very different approaches

There is a large division in the way in which charities can finance their activities from their investment assets, split between those funds that are permanently endowed and those that are not. Permanently endowed charities are only allowed to spend the income earned on their assets whilst the rest can spend capital as well.

In practice many charities which aren’t permanently endowed still only spend income earned and don’t dip in to capital to finance their activities, but there is a growing number which are taking the approach of “spending total returns” (a mix of income and capital), driven in part by the increasing pressure from consultants and others to diversify portfolios. Where this involves diversifying overseas or into government bonds away from UK equities this inevitably leads to a drop in income for the charities concerned.

Stock markets around the world generally yield far less than the UK and the income returns from government bonds have all but disappeared. By way of illustration, the FTSE World Index yields just 2.5% versus the yield on the UK stock market of over 4%, whilst government bond yields are extremely low (and in some cases negative) the world over, except for a few basket case economies.

The UK 10 year benchmark gilt yields just 0.7% at the time of writing, a fraction of the yield on UK equities and well below the current rate of inflation, ensuring that gilt investors planning to hold their investments to redemption will lose significant sums in real terms if inflation continues at its current circa 2% level.

Dangers of spending total returns

Whilst spending total returns is fine in theory, adopting this approach could lead to the erosion of charities’ investment assets to the detriment of future beneficiaries if too much money is withdrawn and also in certain stock market scenarios. This is especially the case where charities take a growing sum from their investment portfolios to cover rising expenses each year.

A low volatile scenario

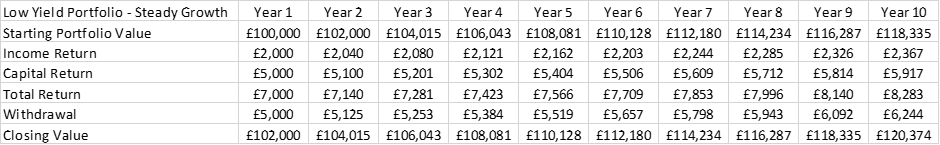

To illustrate this, consider two scenarios relating to the performance of a £100,000 lower yielding charity portfolio where the charity needs to withdraw £5,000 in the first year to cover expenses that are expected to increase by inflation of 2.5% per annum. Firstly, consider a steady growth scenario: the portfolio yields 2% and dividends and capital grow by 5% per annum every year, giving a total return of 7% per annum, in line with the long term total returns from the UK stock market. The portfolio movements over the first decade would look as follows:

Note that the income received from the portfolio’s assets does not grow by 5% per annum for the reason that capital withdrawals are made, reducing the capital base from which the income is derived. In this instance it appears that the charity is financing its costs and growing its assets in a sustainable fashion, ending the period with over £120,000. However, it may come as something of a shock to learn that despite taking out 2% less than the total return initially, the charity would run out of money after about five decades. The trend in the value of the portfolio is shown below:

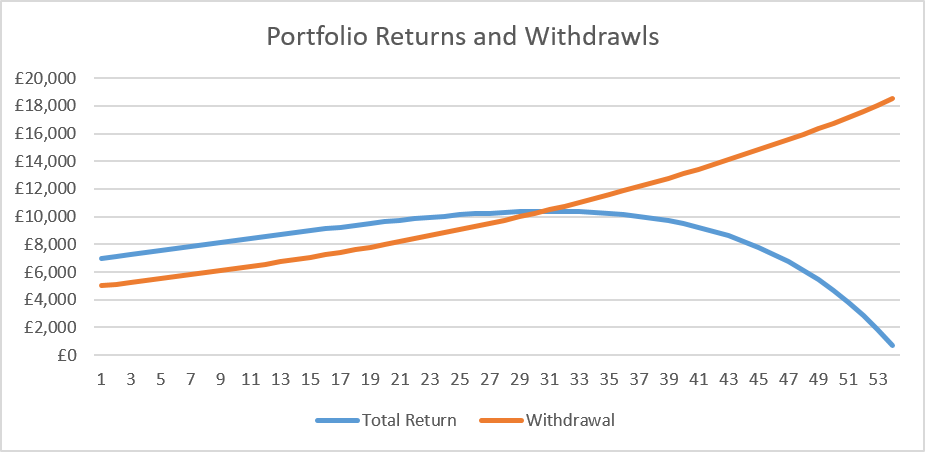

The cause of this somewhat surprising result is that the liabilities (withdrawals) are rising at a faster rate (2.5%) than the portfolio is growing post the withdrawals. Time and the remorseless power of compound interest (if money were borrowed for spending requirements) ensure that, eventually, the growing liabilities overwhelm the investment portfolio, as the following graph illustrates:

Of course charities would react to the potential depletion of their assets by reducing withdrawals but this would mean they had favoured current beneficiaries over future beneficiaries, as this would mean a reduction in charitable activity at some point in the future. It follows that the sustainable levels of withdrawals in this, admittedly unlikely, stock market scenario is £4,500 initially, growing at 2.5% per annum, because this level allows the portfolio to grow by 2.5% per annum as well.

A high volatility scenario

Unfortunately, stock markets do not rise in a predictable uniform manner. Let us suppose the portfolio makes sequential annual capital results of 2.5%, -10%, 7.5%, 0%, 5%, 12.5%, 17.5%, -5%, 12.5%, and 10.7%. Without capital withdrawals this would leave the portfolio at the same capital value (to the nearest £) as the steady 5% per annum growth scenario, ignoring income. The volatile returns and annual withdrawals have quite a marked effect on the value of the portfolio after 10 years, as the following table demonstrates:

In this, more realistic scenario, the capital value grows to just over £111,000 in the ten year period, nearly £10,000 less than in the steady growth scenario. Volatility is not your friend if you wish to spend capital returns, especially if stock market weakness comes at the beginning of the period. The reduction in returns caused by the volatility is the opposite of the well-known investing technique of “pound-cost averaging” where investors that commit regular sums to the stock market and benefit from buying proportionately larger numbers of shares when share prices are low.

Forced sellers at wrong times

Charities which spend total returns end up selling larger numbers of shares to finance their activities when prices are low. In this case the charity will run out of money after 37 years, 16 years before the steady growth scenario. Trustees should be extremely mindful of withdrawing regular growing sums from their investment portfolios. If the initial sum is too great they will be jeopardising their long term investment portfolios and by extension endangering the interests of future beneficiaries.

By way of comparison, volatile share prices in the scenario detailed above mean that the sustainable sum that can be withdrawn from this portfolio is closer to £4,000 initially, growing by 2.5% per annum, than the £5,000 shown in the illustration and well below the £4,500 in the steady growth scenario. Furthermore, knowing the sustainable level of withdrawals in advance is impossible as it would require foresight of future stock market returns and the shape of those returns.

The trustees could withdraw £5,000 initially but they would have to grow the withdrawals at a slower rate than 2.5% to ensure they are not depleting assets in the long run. This would also be to the detriment of future beneficiaries as the real value of the withdrawals would fall.

Just spending the income

To avoid this dilemma trustees could take the permanently endowed approach – just spend the investment portfolio’s income. Of course they would need a higher yielding portfolio to cover the £5,000 withdrawal. Fortunately, the UK stock market is currently providing trustees with a compelling income opportunity. At the time of writing the yield on the FTSE All Share Index is just over 4.1%. This is the average yield.

It is perfectly feasible to assemble a portfolio of higher yielding UK shares, yielding 25% more than this (almost 5.1%) where the underlying companies are growing their dividends at or above the rate of inflation, including, for example, some of the UK’s leading utilities and banks.

Provided the dividend growth from the portfolio overall is higher than inflation, trustees would easily be able to afford the £5,000 annual withdrawal, growing with inflation. There is no depletion of the portfolio as no shares are required to be sold to fund the withdrawals, so the ups and downs of the stock market are irrelevant to the affordability of the withdrawals.

The portfolio would of course rise and fall in value with general stock market movements but the charity’s assets would eventually benefit from the long term rising trend of share prices. There is no need to try and guess what the sustainable level of withdrawals is either.

Income-only spending

There is much academic evidence to suggest that high yield, “value” equity portfolios outperform over the longer term. This has not been the case in recent times when lower yielding growth stocks have tended to dominate stock market performance, but it would be no surprise if high yield stocks gave investors better relative performance in future.

Of course there are high-yielding stocks to be found all around the world, but in lower yielding overseas markets the choice is relatively limited and such stocks are usually in a limited number of stock market sectors. This is not the case in the UK where the choice of potential investments is well spread by sector.

Whether or not trustees are advised to diversify their assets they should think long and hard about moving to a total return withdrawal approach to managing their assets. Injudicious withdrawals will inevitably lead the depletion of investment assets. A far simpler approach exists that does not involve forecasting future stock market returns – just spend your income!