Further investment

Charity investors have to take decisions all the time, whether on investment policy or in connection with their relationship with their investment managers. The articles below help you make these decisions.

Click on the headlines of your choice.

ETHICAL OR SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE INVESTING

FROM THE EDITOR: This special focus on ethical or socially responsible investing (SRI) contains three articles – from Neville White of Ecclesiastical, John Ditchfield of Barchester Green and James Corah of CCLA, all involved in the activities of National Ethical Investment Week, which happens every October. This annual national focus on ethical investing is organised by the UK Sustainable Investment and Finance Association (UKSIF).

The three articles which follow here demonstrate the value of ethical investment to charity investors, provide a guide to being an ethical investor and, above all, move the concept into the more dynamic area of socially responsible investing where the role of charity investors in the relationship between them and the companies they invest in is much more proactive.

It will soon become apparent to any charity reading these articles that they need to get a good grip of this whole concept and their particular involvement in it. Yes, they have to have proper advice but they need to be satisfied that their advisers, i.e. third party fund managers, are operating according to their satisfaction. The last thing an SRI-minded charity wants is for it to be caught wrong-footed by bad publicity emanating from a company it has invested in, whether directly or via a pooled fund.

Why responsible investment should be a priority

Attention is being focused on a quietly thriving part of the UK investment market. In the wake of widespread public disillusion with mainstream financial service providers, ethical and responsible investment products continue to show compelling growth. EIRIS, the ethical research services provider, puts assets under management in over 100 UK ethical or "green" retail products as exceeding £11bn.

For charities, ethical or responsible investment ought to be a default consideration. It supports wider mission objectives and can be favourably aligned with charitable objectives in a holistic way. The way a charity makes or invests its money ought to be as high on the importance list as how those funds are then distributed or spent.

More fundamental purpose

However, ethical or responsible investment can also serve a more fundamental purpose. There is compelling evidence that where integrated into the investment management approach, taking ESG (environmental, social and governance) considerations into account can contribute towards reducing risk and adding value.

This makes the role of informed charity investors all the more important. The faith and other voluntary and charity sectors represent a vital investor pool where performance over the long term, delivered responsibly, is of crucial importance and can help effect wider corporate change.

This focus on integrity, stewardship and responsible business practices that charity investors can bring to the table has never been more urgent. Whether it is excessive executive remuneration, the phone hacking scandal that engulfed the media, or the rigging of LIBOR and product mis-selling in financial services, the seemingly endless failure of business ethics and integrity – "doing the right thing" – is now seldom out of the news.

At the time of writing, the US healthcare giant Johnson & Johnson is reeling from a second massive fine to settle over 7,500 lawsuits, with a total malfeasance bill now standing at over $6bn. GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), among the UK’s largest businesses was handed down a record fine of $3bn as part of the largest healthcare fraud settlement in US history, whilst JP Morgan has agreed to settle a $5bn fine for mortgage mis-selling.

Almost constant scandal

The financial services sector has been engulfed in almost constant scandal recently, but at random, one might cite the record fine of $4.2bn handed down to HSBC for facilitating money laundering in Mexico, and a fine of $667m penalising Standard Chartered for illegal money transfers.

All of these recent corporate scandals have thrown governance risk and wider business ethics failure into sharp relief, proving that mismanagement, poor risk controls and excessive risk taking can, and do, destroy value for companies and investors alike.

It is now clear that the catastrophic explosion in the Gulf of Mexico over three years ago resulted from systemic operational failures on the part of BP and its partners. Liabilities have so far been provisioned at $42bn, more than the UK defence budget, and necessitating a "fire sale" of assets and the downsizing of BP as a business.

It is also clear that the destruction in value has been equally catastrophic for BP investors. This is particularly true of those institutional investors which held the company for its reliable source of dividend income – a dividend that was suspended in the wake of the disaster in June 2010, and not restored until 2011. Whilst the stock has recovered a little, it is still far below 2009 levels.

Poor risk management

What all these corporate events have in common is poor risk management. Because responsible investors analyse companies in a holistic way, considering the entirety of a company’s impacts and risks, including the ESG (environmental, social and governance) factors, a more rounded perspective is often forthcoming.

For instance, responsible investors may tend to avoid extractive industries, including oil, as they largely fail to meet environmental and human rights risk criteria. Instead they may decide to obtain value from accessing the supply chain into those industries.

A series of "events" at BP over many years - including pipeline leaks in Alaska, environmental penalties exceeding the norm, and the explosion at the Texas City refinery in 2005 - would have suggested that BP’s risk profile was unusually high. So by avoiding the stock, investors would have been shielded from catastrophic value destruction following the latest, engulfing, catastrophe.

The way one stock selects can also lead a charity investor to change a position if the ESG risk profile increases in terms of corporate "direction of travel". Until recently it would have been logical to hold the Norwegian champion Statoil as it historically focused on a single market – the Norwegian Continental Shelf – (North Sea oil and gas), had an excellent pollution and safety record, and was leading the way in developing carbon capture and storage technology.

With North Sea reserves in decline however, Statoil made a strategic decision to expand globally, into more challenging territories where human rights risk is material (Libya, Algeria, Angola), and also into unconventional Canadian oil sands which have a high climate change and water use impact.

One would also view "complex offshore" (the term used to define challenging wilderness exploration in the Arctic) as potentially very high risk. So it would be reasonable, listening to the senior management in Oslo, to conclude that the risk profile represented 25% of the Statoil portfolio and was growing. Therefore it wouldn't be surprising if this led to to the conclusion that Statoil was no longer a comfortable fit for ethical funds and disinvestment followed.

Statoil would easily contend for inclusion as a "best in class" stock, but a focus on long term risk and added value would have suggested that over time Statoil could encounter significant problems as a result of its quest to expand into socially and environmentally riskier assets. This has been borne out by a slight increase in the total recordable injury rate and a slight uptick in accidental oil spills from 374 in 2010 to 376 in 2011.

SRI adding value

The case for socially responsible investing helping to reduce volatility risk is complemented by the approach that stock selection based, in part, on ESG factors can positively add value. Let's say one seeks out companies which are not only providing goods and services that people want, but are doing so in a sustainable way.

For instance, the electronics giant Philips may be 120 years old, but it is currently transforming its business from a low growth-low margin consumer electronics business, into one centred on global leading positions in lighting, healthcare and high margin lifestyle consumer products.

Its portfolio is increasingly championing green innovation through its Eco Vision programme in which dedicated "green products" will soon represent nearly 50% of the portfolio by value (€11.2bn at 31 December 2012). This relentless focus on low energy, high performance products has been recognised by the market, and Philips' share price has recovered strongly.

This is where the choice of fund manager as investment partner can make a huge difference for charity trustees. The complexity of many issues may seem daunting for trustees, especially when charities exist to deliver their mission to society rather than improve the corporate world.

Trustees seeking to appoint fund managers should, I would argue, incorporate material ESG risk as part of their tender process. The degree of expertise, understanding and appetite the prospective fund manager has to engage with the companies in which they invest on your behalf should be seen as an important selection differentiator.

Posing straightforward questions

The choice of a fund manager is therefore a crucial one for any charity manager, but some fairly straightforward questions could be posed so that trustees can properly assess the likely interest a prospective manager has in integrating ESG factors into the investment process.

Trustees will want to ask a series of questions in order to understand the underlying ESG risk to their portfolio, and how this is to be managed, given the kind of issues managers are prepared to take action on is instructive. Hopefully, there will be ticks in all the boxes once the questions have been answered, indicating satisfaction with the answers given.

| Are managers voting? |  |

| How are they voting and how active do they appear to be? |  |

| Are trustees in receipt of a complete voting record and do managers publish their voting record in accordance with understood best practice? |  |

| Are they engaging with companies on governance risk and seeking change or improvement where there may be material issues? |  |

| Have they avoided investment on governance grounds and why? |  |

| Is the manager a signatory to the UN Principles of Responsible Investment and the UK Stewardship Code? |  |

| Are they willing to collaborate with other investors around significant issues? |  |

| What types of issue is the manager focused on and what have been the outcomes of any engagement process? |  |

| Is this published? |  |

| Do managers engage internationally? |  |

This list is not exhaustive, but I would contend that in a globalised, complex world which is increasingly focused on resource constraint, climate change and human rights, monitoring ESG risk should be part of trustee due diligence in overseeing their investment advisers and managers. Trustees should routinely question and probe on governance and "non-financial" risk and understand whether managers are active, competent and willing to act proactively in the best interests of their underlying investors on environmental, social and governance issues.

"…mismanagement, poor risk controls and excessive risk taking can, and do, destroy value for companies and investors alike."

"The case for socially responsible investing helping to reduce volatility risk is complemented by the approach that stock selection based, in part, on ESG factors can positively add value."

"…monitoring ESG risk should be part of trustee due diligence in overseeing their investment advisers and managers."

The practicalities of responsible investing

Charity trustees have a lot on their plate. They are ultimately responsible for the difficult decisions a charity makes about which vulnerable people or other cause should receive support. They need significant expertise and experience to make those decisions and usually do so on limited resources.

On top of this, charity trustees are increasingly being asked to make tough decisions about how a charity invests its pension, endowment or other funds. A survey found by the EIRIS Foundation found that 78% of the public think worse of a charity if it invests in funds contrary to its values.

This article seeks to address some of the concerns charities have expressed when it comes to deciding how to invest capital.

Easier said than done

For a busy trustee, aligning a charity’s assets with its charitable mission can seem like another item on an already full agenda. Worse still, it involves entering the highly complex and fraught world of investment. From property to private equity, impact investing to infrastructure, common investments to commodities – investment unfortunately remains an industry that is short on good factual information and long on jargon and strong opinions.

So what are the real facts that trustees and charity managers need to consider if they want to invest in a more responsible or ethical way, or a way that more clearly aligns with their charitable mission?

Statutory obligation to consult

Firstly, trustees do need to consider professional advice from a suitably qualified individual. The Trustee Act of 2000 introduced a clear statutory obligation for all UK trustees (with the exception of trustees of very small organisations) that they must consult with an investment professional before making an investment.

All too often this is the moment where the discussion around ethical, responsible or sustainable investment first flounders – as surprisingly few financial advisers are active in the area. The UK Ethical Investment Association, a membership body for ethical investment advisers, only has around 100 members from the 23,000 independent financial advisers registered in the UK.

Secondly, the law requires charity trustees to be able to justify the adoption of an ethical or responsible investment policy based on one or all of three criteria laid out in the CC14 guidance from the Charity Commission. These three alternative justifications are:

• If a particular investment conflicts with the aims of the charity.

• If the charity might lose supporters or beneficiaries if it does not invest in this way.

• If there is no significant financial detriment.

Setting a clear direction

Thirdly, trustees need to be clear about exactly what the charity is trying to achieve by investing its funds. For example, the objective may be to maximise income, ensure a stable future income or to further the charity’s mission.

Whatever the objective, it should not be an impediment to adopting a responsible or ethical approach. With around 90 "green" and ethical funds on the market there are ways to meet practically all objectives, including the delivery of strong returns or outperformance.

Both profits and principles

The reason most often advanced by trustees for not instigating an ethical investment policy is a perception that it will have a negative impact on returns. However, this reasoning is long outdated and challenged by numerous academic studies and anecdotal evidence.

For example, there is a large environmental campaign group which excludes all large oil and gas companies from their investments. Despite having these screens in place their investments still consistently outperform the benchmark index.

The old stereotype that equates ethical investment with underperformance is also challenged by Steve Kenny, head of retail sales for the Kames Ethical Equity Fund, which is currently ranked first quartile over one, three and five years. He explains: “There is a long standing myth held by many investors that those wanting to invest ethically do so at the cost of performance. Our ethical investing funds have long proven this to be a myth…ethical investors can have their cake and eat it.”

The Kames Equity Fund has returned over 33% in the last year, compared to 26% for a relevant benchmark (IMA UK All Companies). Those interested in emerging markets could turn to a fund such as the First State Asia Pacific Sustainability fund, which has delivered 30% returns over 3 years.

Indeed, there is a strong argument, especially for those investors with a more long term horizon, that it is more risky not to consider sustainability issues when making an investment. That is because companies which don’t manage areas like labour rights, community relations or environmental impact are more likely to be affected by fines, consumer backlashes or regulatory changes which can affect their value.

For example, a recent report by the "Carbon Tracker" initiative found that 80% of the fossil fuel reserves which investors currently treat as assets cannot be burnt if we are to keep global warming within 2°C, meaning the oil and gas companies holding those reserves are likely to be significantly overvalued.

Different types of ethical policy

If charity trustees do decide to adopt a more ethical or responsible investment approach then they also need to be aware of the three different approaches that they can take: "negative screening", "positive screening" and "stakeholder activism". Or in simple terms: excluding, supporting or engaging.

Negative screening means avoiding investment in specific companies or sectors. Positive screening means proactively investing in a theme, company or sector deemed to reflect a charity’s mission.Stakeholder activism refers to a charity using its influence as a shareholder – including exercising its voting rights – to try and improve a company’s performance in a way that reflects its values.

There are many sub-divisions within these general areas. For example the positive screening approach could include investments in a themed fund (such as a renewable energy fund) or could take the form of investments in social enterprises which explicitly produce positive social or environmental outcomes.

Barrow Cadbury Trust, a foundation which supports vulnerable people, recently demonstrated the latter approach by investing £200,000 in Bristol Together, a company which has promised both a decent return and the creation of full-time jobs for ex-offenders and homeless people.

Charities do amazing work to help create a better society, and there is no reason why the £60 billion of assets 1owned by the UK’s registered charities cannot be invested to do likewise.

In the complex world of investment, with the myriad of options and products on offer, trustees may find that using the values and principles of their charity as a guide actually helps make investment decisions a lot more straightforward than they otherwise might be. It could take at least one item off their plate.

"For a busy trustee, aligning a charity's assets with its charitable mission can seem another item on an already full agenda."

"The reason most advanced by trustees for not instigating an ethical policy is a perception that it will have a negative impact on returns."

Engagement and ethical investing

"It is wrong for my charity to exclude investment in certain sectors." 'It is not legal to do so." "It will cost me performance." "We just fund the charity, it is up to the 'mission team' to deliver our aims." "It's a church thing, not for us." These are just some of the myths about ethical investment held in some corners of the charity sector. We have all heard these statements many times, particularly by sceptics. However, as John Ditchfield helpfully reminds us in the previous article, if ethical investment is done properly all of these myths are, well, just myths.

Nevertheless, picking up where John left off, even amongst "the converted" there remains one prevalent myth. That ethical investment is only about setting appropriate ethical exclusions.

Ethical exclusions just the beginning

Do not get me wrong, ethical exclusions are vitally important. They are about identifying the things that contrast most obviously with your charity’s aims, the things that would call into question the reputation of your charity. But they are just the beginning, the foundations of an ethical investment policy, and this is also reflected within the new Charity Commission Guidance.

This says that charity investors should also look to be outward facing with their policies. Indeed the Charity Commission states that “investment managers should vote and engage with company management as a matter of course”.

One way that many charities do this is through engaging with company managements, otherwise known as stewardship of companies. This is done either directly, or more often, through the selection of investment managers which have advanced practices in this area.

Motivations behind conducting employment

The motivations behind conducting engagement take on two forms.

First, many fund managers conduct engagement as part of their approach to integrating environmental, social and governance factors into their investment process. As Neville White has helpfully explained in his article earlier, integrating these factors into an investment process is critical to ensuring, as much as possible, the long term durability of investment returns.

The best integrated policies include both point of purchase considerations and also engagement with companies which are held within the portfolio. This engagement is essential as it guides and shapes companies to help them make appropriate decisions about how to allocate their resources to develop sustained long term returns for shareholders.

This isn't ethical investment, although it comes naturally to investors from that background. It is just "wise investment". Everyone managing money, no matter what their perspective on ethical investment, should be doing it.

The second form of engagement is purely an extension of an ethical investment policy. It is about taking your charity's core mission into the boardrooms of the companies you invest in; using the ownership rights that come with your investments as one lever to try and achieve the change which your charity exists to make. This is a lesser used, but very powerful, approach and can easily be done in several ways including those listed in the following table.

| Engagement technique | Description | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Proxy voting | In the vast majority of cases shareholdings permit investors to vote on the resolutions put to companies' Annual General Meeting. This gives the shareholders the ability to vote on the election of directors, the executive remuneration package, and any proposals placed by other shareholders by way of example. The majority of fund managers will vote their shares. However, leading managers consult their clients to ensure that votes adequately represent their views. | Proxy voting is a relatively time efficient method of engagement. The ability to place votes means that it is easy to engage with many companies irrespective of geographical location. |

| Letter based engagement | Investors can write to companies asking for them to provide information or implement improvements in a particular area of activity. | Letters are an efficient way of writing to a large number of companies. It is an effective way of asking many companies to improve their practices. |

| Meetings | Investors can ask to meet with companies to discuss areas that cause them issues. This practice is normally reserved for larger investors but charities are able to collaborate with other likeminded charities or mandate their fund manager to engage on their behalf. | Face to face meetings are an effective way of generating trust between the investor and company. It allows the development of a mutual understanding on a topic and, over time, progress to be made. |

| Annual General Meeting attendance | Investors are permitted to attend company AGMs and ask questions of the board of directors on any issue. | This is a high profile strategy due to the public nature of the meeting. The tactic is usually the preserve of NGOs and smaller investors who do not benefit from the ability to conduct other methods of engagement. Institutional investors rarely ask questions at AGMs, when they do so it is normally a method of escalating an ongoing engagement. |

Each of these techniques are commonly used by ethical investors and there are good examples of where real change has resulted.

Collective proxy voting initiative

In regards to proxy voting the Church Investors Group, the membership body for 44 church investors predominantly based in the UK and Ireland, have devised a collective initiative that allows them to lodge their votes in a manner that reflects their values. The main focus of this initiative is executive remuneration where they typically do not support two thirds of UK executive remuneration reports due to their belief that executive pay has, typically, become excessive.

The initiative also includes sustainability and diversity factors alongside promoting high standards of corporate governance. By working together these charities have been able to aggregate the impact of their votes as they seek to change corporate practice across the UK market.

Ethical investors have also effectively used letter-based engagement as a method of achieving impact on the scale required to raise standards across the whole UK market. Academics at the University of Edinburgh studied the effectiveness of a collaborative letter-based engagement project conducted by investment managers.

This encouraged companies in the FTSE 350 who had scored poorly on the FTSE ESG Risk Ratings (an independent objective method of assessing companies’ approach to environmental, social and governance factors) to improve their practices. The academics found statistically significant evidence that the engagement had made a difference and raised standards.

More intensive engagement techniques

Ethical investors tend to adopt more intensive engagement techniques when they identify issues of concern at individual companies or in individual sectors. Driving this type of change requires significant time and resources to put into in-depth meetings with companies.

A good example within the UK relates to an international coalition of charities, churches and advocacy groups which worked together to help the two FTSE 100 constituent hotel providers, Whitbread and InterContinental Hotels Group, put in place effective procedures and training programmes to mitigate the risk of their facilities, unbeknown and not condoned by them, being used for the purposes of child sex trafficking.

Following the engagement, both groups instigated training for their staff and franchise holders and consulted expert organisations in setting policy amongst other initiatives. These investors had driven a change in corporate practice.

Finally, investors have effectively used questions at AGMs as an effective method to build upon ongoing engagement that, for whatever reason, requires further momentum and escalation. The public nature of the AGM makes this a high profile tactic but it works best when used in conjunction with other techniques such as those above.

So, ethical investment is not only about ethical restrictions. It can include engagement with the companies a charity invests in as a further lever to deliver that charity's mission. It is a powerful tool in delivering change. However, there remain three misconceptions about engagement itself.

Misconceptions about engagement

The first is that engagement is an excuse for fund managers to invest in companies that charities and their beneficiaries do not want them to. It is beyond doubt that this has happened in some sectors of the market in the past. To avoid this, your fund manager should be able to tell you what it is they are hoping to achieve by any engagement and details of progress made. Leading managers will go one step further and, after time, divest from a company if they are not willing to listen to engagement.

The second misconception is that engagement is a form of campaigning and is confrontational to the company. When done well this is not the case. By having more than a token shareholding in the company, investors are able to show clear alignment. Both organisations want the company to do well and develop profits. They just differ on one area of practice. This alignment allows for the development of trust and partnership and is one of the reasons why investor engagement is such a productive tool.

The final misconception is that only large charity investors can do engagement. This is not true. In practice the majority of charities are reliant upon their fund manager to conduct such engagement. Many do this and it is one of many factors charities can consider when appointing fund managers.

Help from external organisations

Several external organisations also exist to help charities come together to develop practice and encourage collaborative engagement. Church investors have long benefited from the ability to work together through the Church Investors Group and the new Charities Responsible Investment Network offers the same for charities of all backgrounds.

Despite all of the myths of ethical investment it is a powerful tool that can not only protect the reputation of the charity but, when done well, further deliver its charitable purpose through engagement. I recommend you to look at how this may work for your charity.

"…many fund managers conduct engagement as part of their approach to integrating environmental, social and governance factors into their investment process."

"Ethical investors tend to adopt more intensive engagement techniques when they identify issues of concern at individual companies or in individual sectors."

"…your fund manager should be able to tell you what it is they are hoping to achieve by any engagement and details of progress made."

CHARITY INVESTMENT STRATEGIES

How responsive should charity investment strategies be?

FROM THE EDITOR: The aim of this feature is to focus the minds of charity trustees and charity finance directors in particular on how they should plan for the possibility or respond to the actuality of investment markets turning severely downwards after long, sustained rises and to what extent a long term charity investment strategy should have flexibility built into it to deal with turbulence and more than short-lived movements in the other direction.

Just how long should the nerve of a charity investment committee be expected to hold when a market goes in the wrong direction? When is the point that the investment adviser should accept that the charity could have difficulties in sticking with the strategy, e.g. because of a variety of financial pressures coming together? How should investment advisers and charities be working together to address the problem of unexpected sustained market downturns?

We have six contributors who answer these questions in their own individual ways below. They are: Charles MacKinnon of Thurleigh Investment Management, Kate Rogers of Cazenove Capital Management, Adrian Taylor of Smith & Williamson Investment Management , Mike Goddings of Ecclesiastical Investment Management, Tom Rutherford of JP Morgan Private Bank, Christian Flackett of investment firm GAN, and Patrick Ghali of hedge fund advisory company Sussex Partners.

Please scroll down to see each article.

Establish what you are trying to do

CHARLES MACKINNON of THURLEIGH INVESTMENT MANAGERS comments: All charities owe their foundation and genesis to a perceived shortfall in society’s provision for some general need. This need may be very broad, for example provision of care for the elderly, or very specific, such as providing medical care and support for very premature babies.

It is the nature of this charitable aim that generates tension for the trustees in their choice of investments. A well known example is that cancer charities may not wish to invest in tobacco companies, on the basis that the products of these companies are, in part, the cause of the ills which the charity is seeking to cure. This tension has to be balanced with the need of the trustees to provide the best possible outcome for the largest number of possible beneficiaries.

It may be that by rigorously eliminating tobacco and its associated products and services from your portfolio, you so savagely reduce the investment outcomes that the charity is unable to perform its basic charitable aims.

Leaving aside the conflicts of how to invest, there is also the conflict of whether to invest at all, or to invest now. This is where the relationship between the head of the charity, the head of its investment committee and its investment manager is of paramount importance. For most charities there is an almost infinite call on their resources, but there is only a finite amount of return that can be extracted.

As part of the budget process a charity needs to include a detailed projection of likely, best and worst case outcomes from its investment portfolio. This set of possible outcomes should then be strictly attended to when making commitments for future spending, and if this is done, then the whole process is much more resilient to the vagaries of the market.

Recent market movements have highlighted the need for a responsive strategy, with two boom and bust cycles since 2000, and most importantly very low interest rates on cash and short dated bonds over the recent five years. If a charity had held its assets in cash over this period it would have suffered a significant diminution in its ability to perform its charitable aims.

This is where the relationship between the charity and the mandate it gives its investment manager is of paramount importance. The charity has to first establish what it is trying to do in financial terms as opposed to in social terms, and then it must relay this to the manager who may say that the aims are not achievable in the market.

For example, it is not possible to provide a guaranteed return of 10% on your money with no risk to capital in the current market environment. So, if you as the head of a charity want a 10% annualised return, you are going to have to accept some risk to capital, and some variability in the timings of that return.

CHARLES MACKINNON of THURLEIGH says: So what to do today? We have record low interest rates in the UK and the USA, and equity markets have recently once again scaled new highs in nominal terms. If you, as a cautious charity have been sitting in cash for the last five years you have suffered a massive opportunity cost, but should you start to commit capital to the market today? If you, as a well endowed and mature charity have been fully invested and have enjoyed the significant returns from recent equity market rallies, should you be stepping away?

The answer is the same for both: work out what your obligations are, and then work out what you would like to do but will only do if there is funding, and establish a time frame for these aspirations. What you should not do is take a view on the future direction of interest rates or equity market returns, and building your budget around those views.

Invest long term and change infrequently

KATE ROGERS of CAZENOVE CAPITAL MANAGEMENT comments: Beware of the phrases "things are different this time" and "new paradigm". We go in cycles, what comes around goes around. History has a habit of repeating itself. Charities as long term participants in society should not be phased by the endless oscillations. A bit like the experienced grandfather figure, we've seen it all before.

Charity investments exist to help charities further their mission. As reserves, in case of fluctuations in income; or as foundation or endowment assets, generating income to spend on their charitable aims.

Charity investment strategies should be designed for each individual circumstance and should be framed by the ability to tolerate volatility in capital value and the charity’s investment time horizon. Reserve assets tend to have a lower tolerance for moving values and a shorter time frame when compared with foundations and endowments. These are the real grandfathers of the charity investment world.

It is these assets which represent the bulk of charity investments. These charities have very long term time horizons, often with an aspiration for perpetuity, or eternal life. Investment strategies can take a very long term view, giving charities a distinct advantage over other investors such as private individuals or pension funds, who have shorter time frames or defined liabilities. As the adage says, everything comes to he who waits.

So am I proposing a lack of action in charity portfolios? A long term buy and hold strategy? No. I am suggesting that investment strategy should be set with the long term in mind, but I would encourage regular review. Strategy, in investment terms, can be defined as the long term asset mix that best meets the needs of your charity as expressed in your written investment policy.

This should not be changed regularly, unless there is fundamental change either in your own circumstances or in investment markets.Which brings us back to the original question: how responsive should charity investment strategies actually be?

I would argue that the definition of a "fundamental change in investment markets" is at the heart of answering this question. Where the investment world changes fundamentally, charity investment strategies should be rewritten and asset mix changes may be significant. A fundamental change is one that is likely to be permanent, or at least secular not cyclical, i.e. multi-decade not multi-year. One that is factual, not subjective or based on expectations.

An example in recent history might be the broadening of asset classes available to charities over the last two decades. As the number of pooled funds in alternative asset classes - property, commodities, private equity, absolute return - increases, so does the choice for smaller charity investors and the ability for diversification within investment portfolios.

Charity investment strategies should be very responsive to fundamental changes, which should provoke a reappraisal of long term strategy. In addition, a charity investment portfolio should be able to be responsive to shorter term changes in markets, and should have the flexibility to reflect the views of the investment manager and the trustees.

These more subjective views are inherently more uncertain, and the extent of their expression within portfolios needs to be controlled so that a wrong move doesn’t derail the entire long term strategy.

In a period of down equity markets it can be difficult for trustees to stick with a long term investment strategy, but it is also notoriously difficult to time markets. Just as trustees may wish to reduce their exposure to equities in down markets, they will wish to increase exposure in better times. Missing the best 10 days in global equity markets (MSCI World) from 2002 to 2012 was the difference between a return of 69% fully invested, and a return of -5%. It is time in the market, not timing the market that generates returns.

KATE ROGERS of CAZENOVE says: I would advocate charities adopting a strategy and staying the course. The governance of this can be improved by determining worst case scenarios, allowing trustees some comfort that, within a certain range, a period of negative equity returns is a "normal" market event.

So use your position as a long term investor to your advantage. Decide on an investment strategy that best meets your aims, and stick with it. Review regularly, change infrequently and only based on fundamentals. Respond to shorter term market movements to take advantage of opportunities, but do it in a risk controlled manner in order to avoid jeopardising your long term strategy. And don’t panic. Short termism can be a significant detractor to long term value. Unless, of course, it really is "different this time"

Putting investment decisions into a structure

ADRIAN TAYLOR of SMITH & WILLIAMSON INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT comments: Finding a universal investment strategy which is suitable for every charity, and which is unaffected by possible market volatility, is extremely difficult. Each investment decision is unique to every charity and should be considered using three key steps.

First is to set the investment objectives. For this, the trustees should address the charity’s aims as defined in the governing document or scheme, and be prepared to regularly review those objectives.

Second step is to consider risk. Defined in several ways, such as fluctuations in capital and income values, the level of risk to achieve the required return should be agreed by the trustees. They also need to consider the investment timescale which may help to iron out any short term market volatility.

The Charity Commission encourages trustees through its investment guidance notes (CC14) to give significant attention to these issues. These guidelines may help trustees to address a question frequently heard: “After a strong performance in 2013, and given an uncertain global background, should we be seeking protection against a sudden downturn?”

This leads to the third step of assessing the investment outlook. With the future often uncertain, investment managers emphasise the importance of advising charities on the most appropriate solution to match their objectives and approach to risk taking.

In today’s market there is an array of assets available to meet most charity investors’ needs. These include bonds and alternative assets, offering different market characteristics from equities, which can help to deliver smoother, although potentially more modest, investment returns.

There are also synthetic structured products and other derivative instruments, which aim to provide an element of downside protection. However, these may incorporate a capped upside, meaning gains could be restricted if assets rise beyond set limits.

While not possible to control the exact investment outcome it is, of course, feasible to build a portfolio of assets to accommodate a range of probable outcomes and which is in line with your risk/reward requirements. This strategy may need to take into account other factors such as the unwillingness to accept a drop in income, or a fall in capital value, as both may be necessitated in the short term. Alternatively a five year investment strategy will mean that you hold fewer concerns about any short term market volatility.

It is important to maintain flexibility as even a long term strategic investment approach should include the ability to take advantage of short term anomalies or cope with sudden significant setbacks.

The benefit of this approach can be shown through the example of BP, the UK-quoted stock. Until the Gulf of Mexico disaster in April 2010 it represented 8% of the FTSE All Share Index providing 15% of the index’s total income. It was a popular investment with an attractive and consistent income and growth record.

The disaster saw a dramatic fall in share price and a temporary suspension of its dividend which impacted many investors’ income streams.

Those with a diverse and flexible investment strategy may have chosen to sell and invest the proceeds in alternative income stocks and then repurchase BP when confidence returned. Others would have looked to buy on weakness.

Both approaches can have merit and depend upon the trustees’ attitude to risk and reward. It also shows the importance of ensuring that a proportion of the charity’s assets are sufficiently liquid and not tied in for the long term, so that it can respond to unforeseen situations.

This also highlights that while a good stock selection in a portfolio is helpful, a full understanding of the objectives and a risk assessment are necessary to achieve appropriate results.

ADRIAN TAYLOR of SMITH & WILLIAMSON says: This is where a strong relationship, including regular communication, with your investment manager is important, particularly at times of market volatility. They understand the investment outlook and can assess how the probabilities associated with a range of portfolio structures can meet your needs. This should provide for an appropriate investment solution in an uncertain and challenging investment environment.

The trustees must also clearly understand their charity’s investment objectives and ensure there is a strong correlation with the charity’s investment strategy. They have to review regularly their investment strategy and ensure that it remains appropriate, particularly in times of in changing markets.

In reality there is no perfect solution. While predicting the future is difficult an efficient investment strategy should combine a careful analysis of your objectives and requirements over risk and return, while drawing on the skills of an investment adviser.

Getting the investment management agreement right

MIKE GODDINGS of ECCLESIATICAL INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT comments: The noughties were a fraught decade for charities from an investment perspective, with an unusually high number of severe market downturns. Consequently, many new investors will have learned to their cost that timing and duration of investment are as fundamentally important as asset allocation in determining returns.

Not only was it a decade of unpleasant surprises for capital values, for existing investors, it was also one in which it was a struggle to recover lost income resulting from Gordon Brown’s clunking fist punching a 20% hole in equity dividend distributions by removing advanced corporation tax credit.

And since then, heightened volatility has become the norm.

In determining whether and how charities should respond to changes in the market, it is worth highlighting the differences between private investors and charity trustees. Private investors are not bound by charity law; they are able to make decisions in isolation rather than by committee, and as a result can invariably react more quickly.

The degree to which charity trustees can exercise any kind of responsiveness to market conditions will also depend on the type of arrangement they have with their investment manager. Very few managers now facilitate advisory agreements under which trustees can seek advice, and then choose whether or not to act on it. However, this really is the only way that rapid decisions – rightly or wrongly – can be made in the face of changing circumstances.

Most investment managers will operate under a discretionary mandate which enables them to manage the money as they see fit. Risk will often be controlled by asset allocation, with the manager free to move within predefined bands. It is therefore vitally important to ensure that this agreement defines the level of risk or volatility that will be acceptable, and review this in the light of any change in the charity’s circumstance rather than as a reaction to adverse market conditions.

Those charities investing in funds with no encompassing management agreement need to look closely at how they have performed in bear markets. Whilst past performance is not guaranteed to be repeated, it is none the less an indication of how the manager reacts to changing circumstances. For that reason, it is also important to establish whether the same manager is still in place.

The importance of getting it right from the outset – rather than panicking at the first sign of trouble – cannot be overstated. The investment management agreement is there for this purpose, and reputable fund management firms use independent sources to calculate volatility or other measures of risk.

Contrary to popular belief, even the best investment managers cannot forecast the severity and duration of a market downturn, and certainly cannot predict it precisely in advance, so any decision to move out of higher risk assets may be like shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted. Although this may be appropriate if the charity’s circumstances have changed to the extent that further capital losses cannot be tolerated, a simple knee-jerk reaction to continuing bad news may have negative implications for future beneficiaries.

Realising or seeking to cap an unrealised loss by sheltering in a temporary safe haven can pose problems. Ultimately, a decision has to be made to continue the journey towards future capital and income growth when the weather forecast predicts it is safer to venture out into riskier waters. However, the point at which markets revert to positive returns is equally difficult to predict, as is the rate at which they accelerate. The probability of bailing out of a falling market and re-entering it on the rebound at a lower point than when it was exited is inevitably quite low, and can often mean the value of the portfolio will have been eroded for no reason.

MIKE GODDINGS of ECCLESIASTICAL says: Although a market fall of 20% sounds scary, selling 100 shares for 80p simply because they were originally worth £1, and then having to buy them back for £1.10 after the initial rally means you end up with only 73 shares worth £80 instead of 100 shares worth £110. And if each share was producing a dividend of 10p per share, not only have you forgone that income for the time spent sheltering from the storm, your new income will be £7.30 instead of £10 – a 27% reduction when your obligations to future beneficiaries are likely to have increased, therefore further widening the gap.

This is clearly an overly simplistic example, as it takes no account of any gains or losses made whilst sheltering in lower risk assets, nor does it include the costs of sale and purchase, all of which have the potential to improve or worsen the outcome. It does however highlight the advantages of being able to take a longer term view by looking across the valley to the hills beyond, and reinforces the importance of getting the groundwork right.

Focus on risk rather than timing

TOM RUTHERFORD of JP MORGAN PRIVATE BANK comments: There are many good reasons to invest in equities over the long term. As we pass the five year anniversary of the nadir of the crisis – at least in stock market terms – so many will rejoice about the upwards trajectory and a lately improved economic outlook. However, such are the memories of the financial crisis of 2008-9 that others will reflect on the cyclical fragility of markets and hope they are better positioned to cope with any future pronounced downturn.

Of course the charity investment market is a diverse realm so it is perhaps unrealistic to suppose that one size will fit all when it comes to gauging the right level of sensitivity that should be shown. The sector displays huge disparities of wealth and income, seeking to satisfy an equally bewildering array of objectives over very different timeframes.

A lucky few will cite an investment time horizon of many hundreds of years and will bias their endowment asset allocations in favour of riskier assets claiming not to care for the bumps and dips along the road. This institutional thinking borrows from the norms of pension fund investment management, in particular, and provides an academic rationale for onboarding few defensive shifts on a short term tactical basis.

However, this approach was seriously tested during the depths of the recent crisis in the spectre of financial Armageddon and trustees need to be sure about their fiduciary obligations to adopt this line.

It is beyond the infrastructure and capabilities of most charities, indeed of many advisers, to time markets precisely and so it is unrealistic to place too much expectation on this approach.

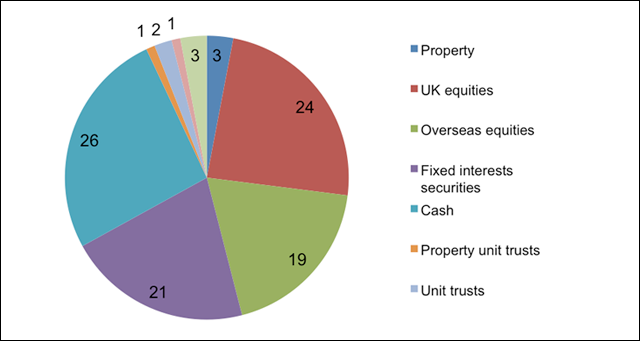

Portfolio construction experts will cite statistics suggesting that over three quarters of long term returns are driven by strategic asset allocation – i.e. the mix of cash, equities, bonds, commodities, hedge funds, property and private equity in any portfolio. The less liquid of these are the preserve of larger portfolios and are not suitable for all charities.

Yet protecting the value of assets during prolonged market downturns does give a powerful compounding effect to long run returns, so some degree of tactical awareness is warranted. Adept advisers will weight portfolios towards or away from riskier assets as the environment suggests. Here a discretionary investment framework offers greater utility understanding that constraints and limits to activism will apply.

Speaking to the usage of hedge funds and structured products specifically, many trustees are hesitant towards such strategies which can serve to reduce overall portfolio volatility and protect capital value during times of market stress. These absolute return orientated mechanisms are usually expensive by comparison to traditional “buy and hold” approaches and often beyond the comprehension of the lay members on the board.

Understandably the less financially savvy may veto such mechanisms. Yet this may import downside risk through reliance on a narrower set of assets or, worse, a misplaced sense of protection through investing in line with observed peer group practice.

Cue a well meaning yet circular discussion as to which risks are appropriate for charities. Simply put there is no clear answer and behind all assets lurk potential dangers: developed equity markets contend with all time highs and uncertain sentiment, while emerging markets reflect the inevitable worries of an uncertain geo-political backdrop; bonds carry duration risk in case rates suddenly increase; and hedge funds and structured products designed to protect value during times of weakness carry illiquidity and issuer default risk. All the while inflation washes away the real value of cash balances.

The point here is not to scaremonger charities away from investing altogether, rather to identify that different asset types assume different forms of risk. With this in mind there is utility in trying to calibrate acceptable levels of risk, and not just expected levels of return, when determining the optimal asset allocation over the long run.

TOM RUTHERFORD of JP MORGAN says: So, if a charity is most concerned about realising its assets at times of stress, then illiquidity and investment default risk may be of greater concern to them. Whereas those more anxious for the nominal loss of capital value – whether or not realised – might have greater concerns for the extent and nature of their equity exposure, potentially increasing exposures to hedge funds or structured products. Those with longer term horizons might not share such worries as explored above.

Those with less income dependency to fund operations may seek to build up cash levels to deploy capital opportunistically at better entry levels as much as a pre-emptive defensive tactic. And so forth.

Both charities and advisers have a duty to think about the likely and possible scenarios and to build their investment portfolios accordingly. Here trustees can help their advisers by clearly stating their priorities so those advisers can think around these specific risks allocations within the portfolio. Within a plural sector different styles and strategies will work better with different charities. Thinking through scenarios works well for all.

Flexibility to absorb short term market strategies

CHRISTIAN FLACKETT of investment firm GAM comments: Charity finance directors and trustees face a complex task in ensuring that they can effectively fund current activities and campaigns, while safeguarding assets for future plans and projects. The sustainability of charities’ business strategies depends on their ability to protect and grow assets throughout the market cycle. This requires taking a long term view, and knowing when to stick with your original strategy despite short term volatility.

Charities must plan for the possibility that the market could experience a downturn after a period of impressive growth following the global financial crisis. Investment strategies must therefore have the flexibility to absorb short term market swings.

Most charities do opt for a diversified portfolio to help protect against market moves - even if equities are at the heart of the strategy. If the portfolio is truly diversified to include non-correlated asset classes, one can reasonably expect a meaningful cushioning of any blow should equity markets suffer a large and/or sustained period of turbulence.

Now that permanently endowed charities can adopt a total return approach without seeking Charity Commission authorisation, trustees are able to include less yield-focussed, non-correlated asset classes such as credit long/short or macro-focused funds.

However, equities remain the most effective way to monetise human ingenuity and deserve to be at the heart of any well-diversified portfolio. 50% in the equities of the portfolio (the growth book) and 50% in non-correlated assets (the capital preservation book) is a useful starting point. This does however vary from case to case – each charity is different and has requirements unique to it. Even a 100% equity portfolio may potentially be appropriate for a charity with a very long time-horizon and no near term funding requirements.

When markets dip past experience tells us that trustees should hold their nerve and ride out the volatility as equity markets tend to regain their losses, even if it takes some time. Capitulating in a trough will only lock in the loss. Non-correlated assets should, however, provide some relief in the meantime.

One of the first things would-be investment managers are taught is to establish the risk profile of their client. As part of this process, the investment manager should ascertain what level of volatility the charity trustees can stomach and make absolutely clear what can happen in a realistic “worst case scenario”, for example a 50% correction in equity markets.

Take for example a charity with a 100% equity portfolio. Then imagine a period of severe equity turbulence which the trustees react to by selling out when the endowment has lost 50%. You can only conclude that the investment strategy was not suitable in the first place for this charity and a more diversified portfolio should have been agreed.

Investment managers must work closely with charity trustees to explain the process of investing. One method which is very effective is regular educational seminars. These should not be events where asset managers sell their services, but rather where they educate trustees on what they can reasonably expect from an investment portfolio.

CHRISTIAN FLACKETT of GAM says: Charities have a right to timely and open communication from their appointed investment managers on the opportunities, dangers and implications of the current investment environment. Portfolio review meetings should ideally be held every six months (and at least annually) to ensure that investment strategy and asset allocation remain suitable. There should be at least two portfolio manager contacts at an investment provider who are well known to the trustees and are available for contact at any point.

Both parties must be cognisant that circumstances can change (for example if a charity which previously required income now needs a more aggressive growth strategy) and it may not be appropriate to wait until the next scheduled review meeting to instigate a change. Some flexibility should always be retained.

One of the key messages is that a carefully constructed diversified portfolio is likely to give you a higher unit of return per unit of risk (a higher Sharpe ratio) and should dampen those peak to trough falls considerably. A diversified portfolio is therefore likely to provide the most sustainable, least volatile returns over the long term.

Charity trustees and finance directors could face considerable financial pressure should portfolios continue to underperform over a sustained period of time, but in most instances they should stay the course. Regular interaction with investment managers is key to understanding recent performance and planning to ensure a strategy remains sustainable. Trustees should avoid making rash investment decisions and have the patience to wait for returns to recover after volatile market episodes.

Hedging out large swings for charity investors

PATRICK GHALI of hedge fund advisory company SUSSEX PARTNERS comments: With the current bull market in equities in its fifth year, many charity boards and investment managers are asking themselves a) should we be more aggressive in our investments to avoid criticism for underperformance, b) should we reduce our exposure to risk, as the bond markets seem to be nudging the bear and every pundit states that stocks cannot continue their feverish pace?

These questions are facing every charity, endowment and pension fund. We have arrived at the proverbial “rock and a hard place”. While many equity markets hit new highs, the China slowdown is worsening, emerging markets currencies are in crisis, and the situation in the Ukraine is suggesting the commencement of a 21st century cold war, with tariffs and embargoes to follow, resulting in economic losses all around. What to do?

In general, but especially in times like these, we feel that there are some basic investment truths that any charity investor should try to remember. They include the benefits of diversification, targeting risk adjusted returns net of all fees, and establishing a balanced risk/return profile to a conservative degree in order to compound positive returns over long periods of time.

But more important than the above is the individual you chose to pursue these aims – the identification of a proven, top performing portfolio manager. Then, let him do his job, in good times and bad.

The fundamental issue is that the majority of paid professional investment managers underperform their respective indices. A recent study in the US compared the returns from 1997 to 2012 of a passive index composed of 60% equities and 40% bonds to 5,000 actively managed portfolios doing the same. 82.9% of the actively managed portfolios underperformed.

Furthermore, one of the objectives that the remaining 17.1% of actively managed portfolios may not be able to solve is market volatility. For this solution you need to turn to those who can effectively hedge out large swings. This means the consideration of alternative asset managers, including hedge funds.

However, hedge funds themselves are not a panacea. Selection is key, and understanding the idiosyncratic risks associated with different strategies, conducting ongoing investment and operational due diligence, and creating a sufficiently diversified portfolio to hedge against the aforementioned volatility all require deep capital pools, significant infrastructure and very specialised skills.

For these reasons, funds of hedge funds rather than single manager hedge funds may be more appropriate for most investors. Additionally, a recent research paper by JP Morgan has looked at funds of hedge funds as a bond replacement, and has found that they may be well suited as such in the current market environment, generating returns that are comparable to BBB bonds with lower levels of volatility. As the rule applies in conventional markets, identification of an outstanding hedge fund of funds portfolio manager can yield extraordinary results.

Above you have the net returns for two fund of funds managers, one regional and one global, superimposed on top of the returns for the underlying markets. The returns speak for themselves. In the end, what one feels these types of managers should deliver year in and year out are "sleep at night” portfolios.

The key to the above graph is the word “net". There is much complaining in the press about a second layer of fees paid to a fund of funds manager, which I feel holds little merit. A fund of funds manager is nothing but a portfolio manager who prefers to sit in his office instead of yours and reap the benefits from his performance.

Furthermore, they hold a few other benefits not visible on the surface – access to closed managers, the ability to negotiate better fee and liquidity terms, and importantly the fact that you as an investor can terminate them much quicker than you could restructure an internal team (typically on monthly or quarterly notice).

PATRICK GHALI of SUSSEX PARTNERS says: Time and time again, one has asked charity trustees and charity chief executives/finance directors to honestly compare the net performance, which means after all relevant internal and external direct and indirect costs, of their existing portfolios against an outstanding (i.e. top performing) fund of funds manager in the same sector. The outstanding fund of funds manager comes out on top.

Many charity investors are most concerned with having confidence in their cash flows. The aim therefore is to compound positive returns on a superior risk adjusted basis with a high degree of certainty.

With the "easy money” having already been made, and given the current level of uncertainty, the difficulty of trying to time markets, the devastating effect of substantial draw downs, and on the other hand the potential risk of missing out on continued upside, considering a more flexible approach may be more prudent, than sticking to a traditional portfolio which may be ill suited to sudden changes.

CHARITY INVESTMENT RELATIONSHIPS

Investment relationships at a time of change

FROM THE EDITOR: This special comment feature looks at what should constitute a good working relationship between a charity and its investment manager, particularly at a time of change. It is in fact an ongoing feature and there will be additional comments published over time. While the contributors may mention the same themes, e.g. good communication and trust, it is refreshing to see how they all discuss them differently, with each article quickly assuming its own separate look and making its own individual impact. Indeed, the articles cover a range of issues, so it is well worth reading all of them.

Knowing the right questions to ask and when

MIKE GODDINGS of ECCLESIASTICAL INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT comments: In an industry which is perceived as being dominated by egos and lacking humility in some quarters, handling the investment manager relationship can be an intimidating task for the chair of an investment committee. Less so if the chair in question has a strong investment background, but other problems can arise if the “lay members” of the committee get left behind, with the chair driving the debate.

Therein lies the risk that human nature being what it is, rather than disagree with a forceful client, an investment manager can allow the discussion to venture into technical territory, unfamiliar to the majority of those present. Whilst the outcomes may be entirely satisfactory, there is always the risk that the obvious questions remain unasked, and when the chair moves on to pastures new, remaining trustees may well have cause to question a legacy arrangement that was a product of individual rather than collective responsibility.

Easier said than done, admittedly, but the moral of the tale is don’t be afraid to ask! The strength of an investment management relationship, or lack of it, can be exposed by knowing the right questions to ask, and knowing the right time to ask them.

Regardless of knowledge and experience, the main thrust of trustees’ interest should be in seeing the capital and income components increase within the agreed risk parameters. And by using the simple expedient of asking what, when, how and why, they should get the answers they need. That's the theory. In reality, it can depend on the type of relationship you have with your investment manager.

Charities with larger investments will invariably have a discretionary, or in a small number of cases, an advisory, or non-discretionary investment management agreement. In the case of a discretionary portfolio, the investment manager will invest the assets in the best way he or she thinks will best meet the charity’s pre-agreed objectives.

A non-discretionary portfolio will be managed on the basis that the trustees decide what they want to invest in, and will periodically seek the investment manager’s advice, which they may or may not choose to take. Clearly any charity with the latter arrangement must feel confident in the ability of its trustees to make these decisions, which is why delegating the responsibility to an investment manager via a discretionary arrangement is a lot more prevalent.

However, this does not absolve the trustees from the ultimate responsibility for ensuring they comply with the requirements of the Trustee Act 2000 – namely to consider whether the individual or collective investments are suitable; are sufficiently diversified, and to regularly review the portfolio to reassure themselves it continues to meet the charity’s objectives.

MIKE GODDINGS of ECCLESIASTICAL continues: Clearly the opportunities to do these things are limited. Investments are by their very nature long term, and short term judgment calls on overall performance, benchmark achievement and therefore whether they meet the charity’s objectives can only be undertaken every few years.

Equally, the voluntary nature of trusteeship means that meetings are infrequent, and therefore it is essential to establish a protocol for dealing with each aspect of these responsibilities. Detailed valuations will normally be produced each quarter providing the opportunity to consider individual stock holdings, review the dividends paid and any changes in asset and market allocation.

The same report for the same period in the previous year, and the prior quarter in the current year should highlight the major changes. Hopefully there shouldn’t be any surprises, but if the majority of the income is now coming from one stock or asset class or if there is a significant variation, now is the time to ask why. Similarly, if after years of investing in recognisable blue chip companies, the portfolio looks to be investing in unfamiliar names or places or Funds, check them out on Google, and then ask why.

Longer term review against objectives should be well prepared in advance, and the investment manager should be aware that this is on the agenda in advance of the meeting. Surprisingly few investment committees ask for a copy of the investment manager’s annual presentation before he or she comes to visit, with the result that their key concerns remain unaddressed.

Requesting a copy in good time before the meeting will not only help trustees frame their questions, it also provides the opportunity for the manager to amend it where necessary and visually illustrate key points in a more convincing way than a simple verbal response which could lead to misunderstanding.

MARK GODDINGS of ECCLESIASTICAL says: A perennial question is what constitutes an appropriate time period for an overall review? The oft given response is around five years, with maybe an interim review at three years, but there is no right answer.

Sometimes it will fall naturally away from the agreed benchmark or investment objective, e.g. to generate an annualised real return against inflation of x% on a rolling five year basis. In which case, this can be assessed annually following the initial five year period, or in the case of an investment in a specific fund, it can be assessed annually.

Some investment managers seek to cover themselves by agreeing to less quantifiable or open ended benchmarks which may not even coincide with the elapsed time period of investment, and thus it is more difficult to establish whether they are doing well or badly.

In such cases it might pay trustees to ask them to break down their performance (or provide an attribution analysis) against the market indices in which they invest, and also against other charity portfolios using reference to independent performance measurement companies such as the WM Company.

Any reluctance to do this should start warning bells ringing. One way of partly resolving the issue of review frequency is to adopt a multi-manager approach, where the portfolio is split between two or more companies who are each tasked with achieving the same overall objective. This can also help trustees with their requirement to ensure adequate diversification where each manager addresses the objective by investing in different markets/sectors and with different exposures to market capitalisation.

This approach not only provides a regular opportunity to make relative comparisons, it also provides greater flexibility in being able to take action sooner rather than later.

Being absolutely clear with the investment manager

HELEN HARVIE of law firm BARLOW ROBBINS comments: The landscape for charity investments has changed substantially for charity trustees, in particular with the relaxing of the duty to invest for maximum return, and with the new concepts of programme related and mixed motive investments. Now more than ever the relationship between a charity and its investment manager is crucial to ensure that both parties understand the requirements for dealing with financial investments in order to develop a fruitful long term partnership.

The best working relationships develop when charities have got the basics right. When creating an investment portfolio, trustees must ensure that they have the power to invest, that they are able to delegate authority to a manager and that the proper processes and documentation have been put in place. Express powers may be contained in the charity’s constitution or there are the statutory powers in the Trustee Act 2000.

Trustees owe a duty of care to ensure that the “standard investment criteria” are met and that they consider the suitability of each particular investment, and the need for diversification in the portfolio. The duty of care is higher for trustees with specialist skills and this may affect those charities with portfolios large enough to warrant having an investment or finance committee.

From the outset, when delegating to a manager, it is vital to have a written investment policy in place, as well as a written agreement which states that the manager must act in accordance with that policy. The terms of the policy and the appointment of the manager must be reviewed regularly.

Good practice suggests that the performance of the investments should be reviewed at least annually and the choice of manager at least every two to three years. As long as the trustees follow these procedures, they will not be personally liable for the decisions of the manager, even if there is a substantial loss in the value of the investments.

The choice of manager is important and affects the relationship that develops. Trustees should look for a regulated firm or individual with a sound reputation, experience in the charity sector and the ability to deal with charity requirements and restrictions. In particular the candidate should demonstrate the ability to deal with smaller portfolios and take a longer term view than most commercial investors.

The trustees are likely to want a tailored portfolio and service, even where the portfolio value is low and they should compare costs, service levels and approaches to investments before making their choice. Spending time choosing the right manager will help reduce the risk of problems later.

HELEN HARVIE of BARLOW ROBBINS continues: A clear investment policy is vital to ensure that the chosen manager fully understands and carries out the wishes of the charity and avoids mistakes which could undermine the working relationship.

The policy should be as full as possible and at the very least should cover: financial objectives; attitude to risk; asset classes and alternative assets; pooled funds or segregated assets (or both); any restrictions on investment powers; any ethical investment requirements; any permanent endowment, restricted funds and reserves; income or capital growth or both; cash needs and timing; target return or total return approach; reporting requirements and performance measurement and benchmarking.

With these basic building blocks in place at the outset, a good manager should be able to develop a trusted adviser role, offering proactive advice on investments and regularly feeding back to the trustees with clear explanations for any changes. The manager needs detailed information and instructions from the trustees, ideally reporting to one key individual.

To perform effectively the manager should gain a clear understanding of the overall objectives of the charity, the time frame for particular investments, the need for income and any particular deadlines during the year, as well as the overall appetite for risk. A manager who is interested in the activities of the charity and listens to the trustees is more likely to be valued.

Regular meetings should form part of the relationship. Face to face meetings avoid misunderstandings and can be helpful in speeding up decision making during times of change. Variations to the original instructions should be confirmed in writing. As well as developing a good working relationship with the main contact, contact with the charity’s accountant is also important to ensure that the charity has the information it requires for its annual accounts.

HELEN HARVIE of BARLOW ROBBINS says: Agreement on the way the performance of the manager is to be evaluated is also of great importance. There are likely to be income/capital growth targets in the investment policy. The manager should be able to show the performance of individual funds against an industry average. Benchmarks such as the WM Charity Fund Monitor or the FTSE All Share Index may be used but only if the comparison is representative. Comparisons with other charity funds operating in the same sector may be more useful.

The best relationship between a charity and its manager is one where both parties are open and clear about their expectations, and have good channels of communication in place to deal unexpected circumstances. The trustees have a duty to set clear objectives and ensure that performance is constantly reviewed and fairly evaluated.