Current investment

Click on the headlines of your choice.

Thinking imaginatively about your financial position

The coronavirus outbreak has been tough on the charity sector. Its income has been severely dented by weaker fundraising and lower investment income, while expenses have remained largely unchanged. At the same time, many charities have seen greater demands on their services as the crisis has exacerbated a number of health and social problems.

As the dust settles and the post-Covid environment becomes clearer, charities need to assess their financial future and the tools they have available to deal with the crisis. It is not all bad news. Necessity can be the mother of invention and charities are finding new and innovative ways to improve their financial situation. Here are some areas that charities may want to examine:

Understand your position

You may have to make some important and difficult decisions. To do that, you need to understand your position in some detail. Do you have enough up-to-date management information to make decisions effectively? It is important to have this at your fingertips or work with your finance team to get it.

Trustees need to consider the charity’s business plan and decide which elements need to be changed, accelerated or curtailed. Long term ambitions may need to be set aside to provide short term protection. Make sure that every member of your team is focusing on the key priorities.

Be realistic about the likely impact on future income and costs, and work with your finance team or external advisers to reforecast your short to medium term cash flows. Talk to your suppliers, fine tune your buying, examine your day to day costs to understand where the charity has flexibility and where it doesn’t.

Scenario planning

You will also need to do some scenario planning. A number of countries which appeared to have the virus under control are now seeing secondary outbreaks and it is important to consider the impact of a second or third wave. While it may be possible to call on reserves for a relatively short-lived interruption in business, it cannot be an effective strategy over the longer term. Trustees will need to consider the viability of specific projects and spending commitments in different scenarios.

Good cash flow forecasting will be an invaluable tool in this process. In tough times this should be based on modelling on a daily receipts and payments basis and for a six week rolling forward timeframe and thereafter for up to six months to show predicted pinch points when further additional funding may be required. This allows charities to be realistic about their future prospects.

Preserve cash

For a charity trying to preserve its long term viability in the face of unprecedented challenges, cash is king. Even as the economies reopen, charities should be looking to preserve cash where possible to give themselves some flexibility and help them deal with potential future lockdowns. This could mean deferring major payments where possible – including capital spending and taxation liabilities – and negotiating with creditors, such as landlords.

If you have recently committed to acquiring new assets for your charity – vehicles, computers, equipment etc. – can these be put on hold to conserve cash? Remember that cash always takes precedence over short term surpluses.

Consider borrowing

A riskier approach is to take on some borrowing, either from government or banks. This goes against the culture of many charities but may be the only option to stay afloat. At all times, trustees need to be aware how much they are paying to borrow, whether it is competitive and how and when it will be repaid.

Your bank should be considered an essential trading partner, so you will need to keep it on side. Highlight any challenges or the likely need for support as early as possible. Be professional, plan ahead for meetings and ensure that any presentations or proposals are clearly set out, detailed, accurate and realistic.

You will also need to consider your long term strategy to get back on track. It may be possible to organise more flexible borrowing facilities that could accommodate any operational disruption from a second or third wave.

It may also be possible to sell assets – either an investment or property portfolio – but trustees should bear in mind that valuations are still depressed and they may not realise as much as they hope. This should be a last resort and should not compromise the long term goals of the charity.

Harness government support

Many charities will have taken advantage of furloughing and sick pay. The furlough scheme has started to be unwound and is no longer open to new entrants. The Government is also progressively unwinding its support on sick pay and charities will need to ask themselves some tough questions on the future of staff members. If staff do need to be let go, start the process as soon as possible – ideally any furloughed staff would leave before the furlough scheme ends.

There is still government financial support available, even if accessing it is competitive. The Government has pledged £750m to support the charity sector, which includes £200 million for the Coronavirus Community Support Fund. The Office for Civil Society is in charge of allocating the pot.

There is also a range of support options for individual charity types: a £14m Zoos Support Fund, managed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs; a Food Charity Grant Scheme, also managed by DEFRA. There is a £30m allocation for domestic abuse charities, plus specific support in other areas including homelessness, mental health, citizens advice, legal advice and vulnerable children.

Business interruption

Charities can also access the Business Interruption Loan Scheme, which gives government-backed and guaranteed loans to support charities and social enterprises with trading revenues. This is designed to support all viable small and large businesses affected by Covid-19, even if they can secure regular commercial financing. However, proving “viability” when the future is so unclear is not easy.

There are also packages put in place by individual sector representatives – the Arts Council England Emergency Response Package, for example, the Historic England Emergency Relief Fund and the Sport England Community Emergency Fund.

Charities need to do their homework to ensure they are not missing out on short term support packages that could make the difference between survival and bankruptcy. It is always worth having a look at the general government schemes available at any given time and seek professional advice if you need further help.

Review your investment policy

Charities’ investment income has also taken a hit during this crisis. Investment income has fallen as companies have cancelled or deferred dividends in order to protect their cashflow in the wake of the Covid-19 outbreak. In aggregate, the dividend income from the UK market could fall by around 40% in 2020.

Charity portfolios will generally fare better because they are not just made up of UK companies or of equities. Many will also include global equities, plus fixed income and alternatives such as infrastructure and real estate. However, it is worth talking to your investment manager to get a sense of how much income might fall and how they are managing through the crisis.

Active management is key for charity investors. Not all companies have been hit equally – the oil majors have been hit hard, while areas such as healthcare and utilities have proved extremely resilient.

Directing an investment portfolio to those areas that are better-placed to weather a dividend storm is a sound strategy amid the current uncertainty. Healthcare and utilities companies yield around 3.5% and over 6% respectively, both little changed from their long term averages. Income investors should also consider looking globally where they can find companies where payouts may be more sustainable.

Above all, diversification is vitally important. This pandemic amply demonstrates how risk can emerge unexpectedly and blindside a portfolio. Diversification – across country, asset class and sector - is a key defence.

Think creatively

This is a new world and calls for big ideas. Trustees will have to be imaginative, at least in the short term. Perhaps the most obvious area is the use of space. Charities will need to examine whether this home-working experiment has changed the way they think about office space: do they need as much? Would capital be better deployed on digitisation and home working solutions? Is it possible to create “pop-up” offices?

There is also the question of what it means for fundraising? Does it finally sound the death-knell for the expensive and inefficient fund-raising tool of shaking buckets in a town square? Captain Tom Moore showed the incredible power of social media and a good story when he raised £32m for the NHS.

Trustees will need to look closely at the cost of raising funds and focus on those areas that give them the greatest bang for their buck. A number of charities have teamed up with their peers with similar missions to share resources and this may be another solution to consider.

When all is gloom

It may look like there is no way out, but sometimes the right advice at the right point can help a charity survive. The new Corporate Insolvency and Governance Bill, currently passing through Parliament, will give charities in financial difficulties more options, protecting them against creditor action and giving them some breathing space to address financial problems. There may be solutions even where the outlook looks extremely gloomy.

"Make sure that every member of your team is focusing on the key priorities."

"There is still government financial support available, even if accessing it is competitive."

The active versus passive debate for charity investors

Passive investments have been used for decades, but in recent years many investors, including charities, have turned to passive strategies on a scale never seen before. The huge growth in passive investment is one of the defining features of the current bull market and is helping funnel flows into areas that are already very popular. However, in certain asset classes and investment styles this increases the likelihood of significant losses when the trend changes.

Charity trustees have a duty to act in the best interests of their charity; they also need to bear in mind the impact of their choices on beneficiaries. The debate over whether to pursue active or passive investment strategies could make a significant difference to a charity’s costs and risk profile – and thus the returns available for use by the charity.

Active asset management uses a human element to “actively” manage a fund’s portfolio, using research and judgment to make decisions on which securities to buy, sell or hold. In contrast, passive investments are low cost strategies that typically aim to track an index, such as the FTSE 100 or the S&P 500 index.

Mixed situation about passives

Passive managers have expanded their offerings to include active-style strategies that require frequent rebalancing, but are marketed as passive, such as factor investing. Investors need to be very aware of the underlying index their passive fund is tracking. Different providers may well offer the same named passive trackers though the underlying indices can be very different.

Passives are beginning to have considerable impact on the marginal pricing of stocks, market volatility, cross-correlations and price discovery.

There is no strategy or asset class in the world that can’t be ruined by having too much money thrown at it, and a fundamental concern with passives is that they can channel money into areas that have already performed very well. Are investors confusing low cost and no active decisions with low risk? Moreover, passive management makes no attempt to distinguish attractive from unattractive securities - and makes it more difficult for an investor to target a specific required return to meet an income requirement for example, as this would usually entail taking a certain degree of active risk.

The case for passive investment

In a lower expected return environment, the low fees involved in passive investing are clearly attractive. Many of these vehicles are very large, and therefore benefit from considerable economies of scale. Passives do not incur the usual expenses required for active management. and can engage in strategies which can help reduce their cost base. Examples such as lending stock to short sellers for a fee and making a profit on the bid-offer spread on their high daily turnover are often employed as cost reduction strategies.

Disappointment surrounding active manager performance has further driven investors towards passive vehicles, as the current bull market has led to a number of active styles - such as value investing - struggling to keep up with a momentum driven market. In addition, too many active funds have pursued tight benchmark tracking strategies and thus the active industry as a whole has failed to add enough value through outperformance to justify its higher fee structure.

The popularity of passives has also been encouraged by the low interest rate environment that we’ve experienced since the global financial crisis. The collapse of bond yields has forced risk averse investors into equities to replace their income shortfall. These investors have favoured bond proxy and low volatility strategies, and as these have grown in popularity, they have built a self-perpetuating momentum of their own.

Bull markets and passive

It is argued that many of the equity market returns since 2009 have been driven by central bank policy, quantitative easing and low interest rates, and that these factors have overridden other considerations. As is often the case when optimism returns to markets, many of the higher risk stocks were those that grew the fastest.

However, actively managed portfolios grew at a less dramatic rate than portfolios invested in index tracker funds, partly due to human fund managers being much more aware of potential risks and using caution when investing. Index returns can be skewed by the excess returns of a few stocks, the rise of the impact of the FAAMG (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Google) stocks on the US markets being a good example. Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Google and Facebook currently make up around 17% of the S&P 500 index.

It is important to remember that no bull market has lasted forever, nor is there any reason to suppose that the bear market has been banished indefinitely. Over the long term, valuation is the core driver of the market, not sentiment, yet the more a charity pays for each share, the harder it is to generate long term profits. Market indices are substantially higher than they were in 2009, which suggests expected index returns in the coming years are likely to be far lower than in the recent past.

Planning for the future

Timing is vital in capital markets. Many charity trustees focus on near term performance relating to the last three to five years. However, what trustees must consider is the importance of seeking data that covers both bull and bear markets. The current bull market extends back to 2009, but to include a full cycle you should include the last bear market and as such data must start in 2007, the peak of the last cycle - meaning that a complete and meaningful picture is shown. That is thirteen years of data, rather than five.

To illustrate the significance of this, we should consider what happens over the course of a market cycle. Towards the end of a bull run, the range of successful investments begins to narrow. Investors find themselves increasingly funnelled into a narrower range of assets, placing more and more of their investment into a few selected crowded stocks. This naturally increases stock specific risk within a portfolio, an undesirable situation for charities seeking lower volatility and consistent returns.

While it is not known when this bull market will end, trustees seeking outperformance over the long term are well advised to select investment managers that can demonstrate respectable performance during market lows, as well as market highs.

Managing capital loss risk

Long term investors would see risk as being permanent loss of capital rather than volatility or benchmark tracking error. They can manage this risk in two key ways.

Avoiding big losses is more important than picking big winners. In a period of technological change, a large number of companies and sectors face technological disruption. Highly indebted companies or those with poor corporate governance are especially vulnerable. Many businesses are facing material threats even though their shares are still trading on very high multiples.

Often these risks are not being reflected in share prices and it is possible that passive investing is supporting the share prices of companies whose fundamentals do not support current valuations, thus creating price distortions. By being more selective with stock picks, focusing on high quality companies operating in profitable and growing industries, one can exclude high risk businesses which would be impossible to avoid when investing through index trackers.

Portfolio balance is the second way that one can seek to reduce the risk of permanent loss of capital. Portfolios can be tilted to the outcomes seen as the most probable but should be constructed to ensure a spread of exposures that would do well in the event of the unexpected.

When considering an appropriate investment strategy, trustees must ask themselves: does blindly allocating capital according to market capitalisation, while concurrently ignoring valuation measures and business fundamentals, really accord with the fiduciary duty of trustees?

Historically, passive management has peaked in popularity near the top of the cycle. In contrast, active managers, who can be more selective with their portfolios, tend to perform better than passive strategies in down markets, particularly with regards to protecting capital.

Quality active management

So the conclusion has to be that there is value to be found in a quality actively managed portfolio, particularly during more volatile periods for markets. It is undoubtedly true that there is value in holding passive investments given that their structure can offer exposure to specific sectors or geographies at very low cost. However, these should be viewed as most beneficial when used tactically, as part of the asset allocation of a sensible and well diversified actively managed portfolio.

"There is no strategy or asset class in the world that can’t be ruined by having too much money thrown at it, and a fundamental concern with passives is that they can channel money into areas that have already performed very well."

"Market indices are substantially higher than they were in 2009, which suggests expected index returns in the coming years are likely to be far lower than in the recent past."

The impact measurement revolution

It is increasingly clear that to meet the challenges of the climate emergency and address social problems, good intentions are not enough. Against this backdrop, the latest frontier in responsible investment is impact investing. This is investing to produce a tangible goal, such as lower emissions, labour reforms or clean water. Today, the market for investments designed to create a positive social or environmental outcome is $715bn in size and rising fast.

For charities, there is a growing body of evidence that this approach can not only boost financial performance, but also enable them to align their investments with their charitable aims.

It can help expand their mission: a child welfare charity can invest in companies which are tackling child labour, environmental charities can ensure that their investments help reduce carbon emissions or encourage biodiversity. Impact investment is a way for a charity to deliver more than it could through its day to day activities.

The Charity Commission’s guidance on this area for financial investments is being revised but they are waiting for the outcome of two High Court cases due any minute which will update the case law. The Charities (Protection & Social Investment) Act 2016 widened the options for charities to use their assets in a way to further their aims and make some financial return through programme related investment and mixed motive investment.

Understanding impact investment

It is impossible to deal with the scale and severity of the social and environmental challenges faced globally without harnessing the resources of the private sector. As shareholders – and as allocators of capital – charities can exert powerful influence on companies’ behaviour. They can pour money into enterprises creating measurable impact, while draining resources from those companies creating environmental or social harm.

The old model, which put shareholder primacy at the top of the tree, has not encouraged this behaviour. If anything, it encouraged wasteful use of natural resources or human capital in pursuit of profit above everything else. To create the change needed, a wholesale redesign of the capitalist system is required, from one of shareholder primacy to one of stakeholder primacy. Charities should be at the forefront of this shift.

It means that shareholders, customers, employees, the environment and wider society all become part of an organisation’s purpose. For organisations, being able to demonstrate real positive impact both qualitatively and quantitatively will be a major differentiator. It will influence the extent to which they can attract capital, and the cost of that capital.

It is also likely to see new types of enterprise emerge, led by entrepreneurs with different priorities. These are likely to be able to attract capital, scale up and deploy resources much faster and further than before, and thus achieve much more impact. Those which can’t show positive impact will face higher costs and will be left behind. The charity sector will be no different. New types of charities will emerge with new objectives. It is a new environment, for which trustees need to be ready.

The systematic reporting of positive and negative environmental and social impact is a starting point to harness market forces and create enduring change. Investors and regulators are increasingly starting to demand more granular data. This measurement is where the revolution starts. All public and private organisations including charities will ultimately need to be included in this transformation.

The impact sector is still small, but has accelerated recently, growing more than three-fold in just two years, according to the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN). With new capital, the sector has evolved, spreading from the high net worth/philanthropist market to institutional and then retail investors.

Defining and measuring impact

The term “impact investing” is still relatively new, coined in 2007. The philosophical premise is relatively straightforward - to balance financial returns and positive social or environmental impact. Impact investors will consider a company's commitment to corporate social responsibility and how it interacts with society as a whole.

However, there are some obvious challenges. A system of measurement and reporting has had to be constructed from scratch. This is still work in progress and it will take time to get it right, but policymakers, regulators and accounting institutions are working to define and cost exactly what constitutes environmental and social impact, both good and bad, and how this can be incorporated into the accounting standards of each organisation.

To date, we have seen the EU taxonomy (list of environmentally sustainable activities), the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the G20’s Taskforce on Climate Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), all of which are helping to create a framework that allows for greater measurement of impact. In the UK, the government has pledged that TCFD reporting will be mandatory across the country by 2024/5; and for larger entities (FCA rules) the mandatory reporting starts from 1 January 2021.

While the early iterations of SFDR were watered down, regulators are unlikely to defer indefinitely and more stringent disclosure and reporting rules are expected shortly. The EU already has its environmental taxonomy, which is due to come into effect later this year, which gives it a good framework for similar efforts on measurement on social issues.

Amit Bouri, GIIN chief executive, wrote earlier this year: “In 2010, most [investors] used their own systems to track impact outcomes. Now, almost all are aligning around a core group of [impact measurement and management] systems.” The GIIN has developed its own IRIS+ system, which provides data to gauge whether investments achieve their social and environmental goals.

In 2019, the International Finance Corporation, the private sector division of the World Bank, launched a framework called the Operating Principles for Impact Management. The IFC principles are more stringent than the GIIN rules, largely because the information has to be vetted by an external auditor.

The Harvard Impact-Weighted Accounting standard has also had a significant impact. On launch, Harvard said: “The mission of the Impact-Weighted Accounts Project is to drive the creation of financial accounts that reflect a company’s financial, social, and environmental performance. Our ambition is to create accounting statements that transparently capture external impacts in a way that drives investor and managerial decision making.”

Broadening of measurement

Measurement is broadening out. Early on, the environment has taken centre stage. It is relatively easy to report on carbon output, to set targets for reduction and to see whether those targets are being met. The same is true on biodiversity or water targets, though these are at an earlier stage of reporting and measurement.

However, the “S” (social) in ESG is becoming more important. As the Covid-19 pandemic hit, citizens became more tolerant of government intrusion into their lives. Expectations have changed, and this is likely to accelerate social impact measurement too. This is still in its infancy in the UK and there are challenges around disclosure – can companies measure the social diversity of their staff, for example? What measurements can be put in place to judge wellbeing?

That said, there is progress in this area, and it is likely to be a major focus over the next 12 months. The EU has already published a first draft of a social taxonomy. Progress may be slow, but this change is coming.

The impact for companies

In the longer term, as these frameworks become more widely used, the “impact” of an organisation will have a greater bearing on its value. With standard rules agreed across the globe and accounts weighted in a standardised way, within a decade all investors and all projects could be routinely screened against risk, return and impact. The aim is to galvanise companies into more responsible behaviour.

GIIN’s Bouri has said: “We cannot unsee what this past year has revealed. There will be no miracle cure, no silver bullet for the economic and social recovery ahead. Instead, to truly address the underlying problems exposed by the pandemic, we need to tackle our systemic gaps from more than one direction.”

On the other hand, it becomes more difficult for non-compliant companies to raise capital. Increasingly, more assets will be managed under the impact umbrella and companies will be judged on their social and environmental impact. This is ultimately likely to be reflected in share prices. . If a company’s impact is clear, it will be more difficult for investors, particularly those that need to answer to other stakeholders, to be conspicuously committing capital to companies with a negative or social impact.

This is likely to accelerate a process already taking place, whereby “bad” companies with poor impact scores are likely to see a higher cost of capital. This will make them less competitive and less able to invest to achieve wholesale change. For charity investors, there is not just an ethical argument for prioritising companies with good impact, but also a financial one.

A more sophisticated measurement of impact will go some way to addressing the pernicious problem of greenwashing. It should help ensure that governments and companies deliver on their promises. It is clear to many responsible investors that those companies with large, well resourced investor relations team are adept at delivering the highest ESG scores. With impact measurement, it is far more difficult to greenwash a company’s output. As impact reporting becomes more important, companies have fewer places to hide.

Trustees preparing now

As a trustee, you need to be aware that this is coming. Charities have been at the forefront in terms of reporting impact and therefore the measures being put in place should not be unfamiliar. Increasingly companies are reporting in a more sophisticated and granular way, which makes it easier for charities and their advisers to quantify the impact of their portfolio.

Equally, there is plenty of information on impact investment. The TCFD website is a useful source of information about governance. The Charities Commission revised its Charity Governance Code in 2020. We see standards going up across the sector.

That said, charities may also need to be prepared for bad news. Impact scores for publicly quoted companies in their portfolios may not be as hoped. It is worth remembering that we are only in the foothills of this new way of viewing corporate purpose. For companies, their willingness to engage, and to address areas of weak performance may be every bit as important as their initial scores. In the early days, impact scores are about quantifying the extent of a problem, rather than trying to achieve the lowest score possible.

This is an exciting new dawn in investment. Suitability and diversification requirements will not change but for charities it will become easier to make the same impact with their investment portfolio as they make with their day to day activities. It will be easier to blend the goals of the charity within an investment portfolio. It will not happen overnight, but the change will be profound.

"Investors and regulators are increasingly starting to demand more granular data."

"…within a decade all investors and all projects could be routinely screened against risk, return and impact."

"A more sophisticated measurement of impact will go some way to addressing the pernicious problem of greenwashing."

How charities can avoid running out of investment money

Charity investment portfolios deliver the income and investment returns that fund long-term projects, but rising pressure is leading to unsustainable spending strategies that could cause charities to ultimately run out of money.

Two very different approaches

There is a large division in the way in which charities can finance their activities from their investment assets, split between those funds that are permanently endowed and those that are not. Permanently endowed charities are only allowed to spend the income earned on their assets whilst the rest can spend capital as well.

In practice many charities which aren’t permanently endowed still only spend income earned and don’t dip in to capital to finance their activities, but there is a growing number which are taking the approach of “spending total returns” (a mix of income and capital), driven in part by the increasing pressure from consultants and others to diversify portfolios. Where this involves diversifying overseas or into government bonds away from UK equities this inevitably leads to a drop in income for the charities concerned.

Stock markets around the world generally yield far less than the UK and the income returns from government bonds have all but disappeared. By way of illustration, the FTSE World Index yields just 2.5% versus the yield on the UK stock market of over 4%, whilst government bond yields are extremely low (and in some cases negative) the world over, except for a few basket case economies.

The UK 10 year benchmark gilt yields just 0.7% at the time of writing, a fraction of the yield on UK equities and well below the current rate of inflation, ensuring that gilt investors planning to hold their investments to redemption will lose significant sums in real terms if inflation continues at its current circa 2% level.

Dangers of spending total returns

Whilst spending total returns is fine in theory, adopting this approach could lead to the erosion of charities’ investment assets to the detriment of future beneficiaries if too much money is withdrawn and also in certain stock market scenarios. This is especially the case where charities take a growing sum from their investment portfolios to cover rising expenses each year.

A low volatile scenario

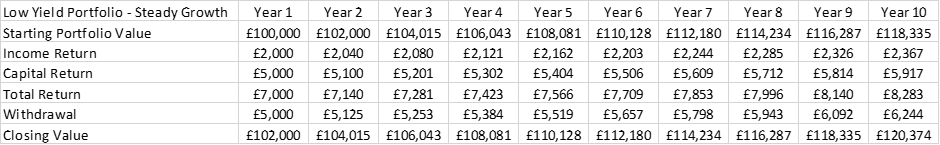

To illustrate this, consider two scenarios relating to the performance of a £100,000 lower yielding charity portfolio where the charity needs to withdraw £5,000 in the first year to cover expenses that are expected to increase by inflation of 2.5% per annum. Firstly, consider a steady growth scenario: the portfolio yields 2% and dividends and capital grow by 5% per annum every year, giving a total return of 7% per annum, in line with the long term total returns from the UK stock market. The portfolio movements over the first decade would look as follows:

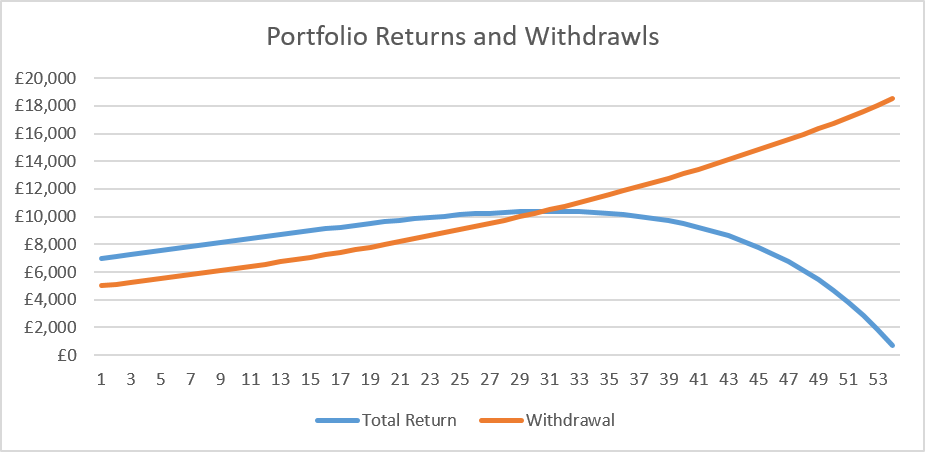

Note that the income received from the portfolio’s assets does not grow by 5% per annum for the reason that capital withdrawals are made, reducing the capital base from which the income is derived. In this instance it appears that the charity is financing its costs and growing its assets in a sustainable fashion, ending the period with over £120,000. However, it may come as something of a shock to learn that despite taking out 2% less than the total return initially, the charity would run out of money after about five decades. The trend in the value of the portfolio is shown below:

The cause of this somewhat surprising result is that the liabilities (withdrawals) are rising at a faster rate (2.5%) than the portfolio is growing post the withdrawals. Time and the remorseless power of compound interest (if money were borrowed for spending requirements) ensure that, eventually, the growing liabilities overwhelm the investment portfolio, as the following graph illustrates:

Of course charities would react to the potential depletion of their assets by reducing withdrawals but this would mean they had favoured current beneficiaries over future beneficiaries, as this would mean a reduction in charitable activity at some point in the future. It follows that the sustainable levels of withdrawals in this, admittedly unlikely, stock market scenario is £4,500 initially, growing at 2.5% per annum, because this level allows the portfolio to grow by 2.5% per annum as well.

A high volatility scenario

Unfortunately, stock markets do not rise in a predictable uniform manner. Let us suppose the portfolio makes sequential annual capital results of 2.5%, -10%, 7.5%, 0%, 5%, 12.5%, 17.5%, -5%, 12.5%, and 10.7%. Without capital withdrawals this would leave the portfolio at the same capital value (to the nearest £) as the steady 5% per annum growth scenario, ignoring income. The volatile returns and annual withdrawals have quite a marked effect on the value of the portfolio after 10 years, as the following table demonstrates:

In this, more realistic scenario, the capital value grows to just over £111,000 in the ten year period, nearly £10,000 less than in the steady growth scenario. Volatility is not your friend if you wish to spend capital returns, especially if stock market weakness comes at the beginning of the period. The reduction in returns caused by the volatility is the opposite of the well-known investing technique of “pound-cost averaging” where investors that commit regular sums to the stock market and benefit from buying proportionately larger numbers of shares when share prices are low.

Forced sellers at wrong times

Charities which spend total returns end up selling larger numbers of shares to finance their activities when prices are low. In this case the charity will run out of money after 37 years, 16 years before the steady growth scenario. Trustees should be extremely mindful of withdrawing regular growing sums from their investment portfolios. If the initial sum is too great they will be jeopardising their long term investment portfolios and by extension endangering the interests of future beneficiaries.

By way of comparison, volatile share prices in the scenario detailed above mean that the sustainable sum that can be withdrawn from this portfolio is closer to £4,000 initially, growing by 2.5% per annum, than the £5,000 shown in the illustration and well below the £4,500 in the steady growth scenario. Furthermore, knowing the sustainable level of withdrawals in advance is impossible as it would require foresight of future stock market returns and the shape of those returns.

The trustees could withdraw £5,000 initially but they would have to grow the withdrawals at a slower rate than 2.5% to ensure they are not depleting assets in the long run. This would also be to the detriment of future beneficiaries as the real value of the withdrawals would fall.

Just spending the income

To avoid this dilemma trustees could take the permanently endowed approach – just spend the investment portfolio’s income. Of course they would need a higher yielding portfolio to cover the £5,000 withdrawal. Fortunately, the UK stock market is currently providing trustees with a compelling income opportunity. At the time of writing the yield on the FTSE All Share Index is just over 4.1%. This is the average yield.

It is perfectly feasible to assemble a portfolio of higher yielding UK shares, yielding 25% more than this (almost 5.1%) where the underlying companies are growing their dividends at or above the rate of inflation, including, for example, some of the UK’s leading utilities and banks.

Provided the dividend growth from the portfolio overall is higher than inflation, trustees would easily be able to afford the £5,000 annual withdrawal, growing with inflation. There is no depletion of the portfolio as no shares are required to be sold to fund the withdrawals, so the ups and downs of the stock market are irrelevant to the affordability of the withdrawals.

The portfolio would of course rise and fall in value with general stock market movements but the charity’s assets would eventually benefit from the long term rising trend of share prices. There is no need to try and guess what the sustainable level of withdrawals is either.

Income-only spending

There is much academic evidence to suggest that high yield, “value” equity portfolios outperform over the longer term. This has not been the case in recent times when lower yielding growth stocks have tended to dominate stock market performance, but it would be no surprise if high yield stocks gave investors better relative performance in future.

Of course there are high-yielding stocks to be found all around the world, but in lower yielding overseas markets the choice is relatively limited and such stocks are usually in a limited number of stock market sectors. This is not the case in the UK where the choice of potential investments is well spread by sector.

Whether or not trustees are advised to diversify their assets they should think long and hard about moving to a total return withdrawal approach to managing their assets. Injudicious withdrawals will inevitably lead the depletion of investment assets. A far simpler approach exists that does not involve forecasting future stock market returns – just spend your income!

"Trustees should be extremely mindful of withdrawing regular growing sums from their investment portfolios."

"…knowing the sustainable level of withdrawals in advance is impossible as it would require foresight of future stock market returns and the shape of those returns."

Positioning ESG in the investment process

Charity trustees could not be blamed for feeling somewhat overwhelmed by the tidal wave of ESG (environmental, social and governance) information washing over them. This has led to some confusion regarding to what extent ESG should be viewed as a nice to have or whether it is something more significant which charity trustees are under a positive obligation to consider when carrying out their investment duties.

This is often because ESG is spoken about in the same breath as social investment – where a charity may use its investments to advance their charity’s mission – or it is perceived to be a new way to describe ethical screening, the screening out of tobacco for cancer charities being the most obvious example.

Whilst ESG (environmental, social and governance) is a close relative of both ethical screening and social investment, it is not the same animal as it is concerned not only with the ethical and societal implications of an end product, like tobacco, but also:

- It requires a level of visibility over what level of ESG practice has been observed in the methodology by which that end product was produced.

- Beyond that it requires an understanding of the potential financial performance or value implications for that investment as a consequence of that methodology.

In determining whether or not an ESG approach is a nice to have or a fundamental requirement, it is first helpful to reflect on the statutory and fiduciary obligations to which charity trustees are subject and consider how those might apply to ESG investment decisions.

Trustee investment duties

When considering how to exercise their investment powers, charity trustees should have regard to their investment duties, which have been codified in the Trustee Act 2000 and comprise the following: a duty to consider the suitability of the investments; a duty to consider the need for diversification; a duty to obtain and consider proper advice before investing.

Technically, the Trustee Act 2000 only applies to trustees of unincorporated charities and not directors of charitable companies. However, both the Charity Commission and HMRC apply these principles in their assessment of trustee investment decision making, which means that they effectively apply to all charities regardless of form.

As regards the question of “suitability”, the Commission, and indeed case law, has made it clear that it would include an assessment of “any relevant ethical considerations”, which I explore further below.

In terms of charities which are companies, the Companies Act 2006 includes additional considerations for company directors, requiring them to have regards to: the impact of the company’s singular operation on the community and the environment; the desirability of the company in maintaining a reputation for high standards of business conduct; the likely consequences of any decision over the long term.

The overarching point to keep in mind in relation to these duties is that they are there to help regulate the level of risk, highlighting that such matters should not be considered exclusively through the prism of financial considerations.

Whilst having regard to non-financial matters when considering risk is not particularly a new idea, given the extent to which we now see social and environmental interests shaping economic policy, not to mention catalysing protests in the streets, their relationship to financial value has never been more significant.

Risk to financial value

There is now a body of credible evidence demonstrating that ESG (environmental, social and governance) considerations have a role to play in the proper analysis of investment value. One can envisage a number of circumstances where a company’s failure to have appropriate regard to ESG considerations may expose it to a higher level of risk than a more ESG focused equivalent.

To give a few examples:

- A firm which produces a high level of emissions during a manufacturing process may be exposed to potential future legislation or the introduction of a carbon tax.

- A firm which poorly treats its employees or suppliers may face a backlash from its consumers and see its sales fall.

- A firm with poor governance may become embroiled in a scandal that ultimately leads to its downfall.

Charities are not alone of course in endeavouring to assess whether certain assets, particularly carbon-heavy assets, may be subject to economic considerations which may impact on financial performance. Indeed, we have seen a whole raft of regulations and policy initiatives emanating from the Bank of England, the Pensions Regulator and the Law Commission etc, all of which recognise the importance and magnitude of the risk to financial stability posed by climate change.

Of course, ESG is not all about the environment. The governance failings of Volkswagen concerning its gaming the system in respect of diesel emissions resulted in a 30% drop in share price and massive reputational damage that lingers on to this day.

It follows therefore that even where trustee boards may be indifferent to the plight of polar bears or the proliferation of plastic bags, it is nonetheless incumbent upon them to understand the positive correlation between financial performance and ESG considerations which, of itself, might justify favouring investments which are less exposed to ESG risks.

Not charities’ best interests

Whilst the potential risk to financial value is reasonably straightforward to understand, subject to having the financial data available to support the position. The extent to which non-financial matters should be taken into account in a charity context is perhaps more difficult to judge.

This is in part due to the case of Cowan-v-Scargill which is still often interpreted as imposing a blanket duty to obtain the maximum rate of return possible, effectively precluding trustees and their fund managers from having regard to any considerations other than the maximisation of financial returns.

However, the position is a good deal more nuanced and there are exceptions to this basic rule by which trustees may give effect to matters which go beyond pure financial return.

Contradictory to charities’ objects

The position was clarified in the Bishop of Oxford case, in which the judge declared that trustees could reject any investment, regardless of the financial consequences, if the investment conflicted with the objectives of the charity.

It is clear that the impact of climate change has much wider, far reaching implications, for a broader spectrum of charities than, say, the question of tobacco. Companies which contribute to climate change may potentially impact a huge number of beneficiaries across a range of charitable activities, extending far beyond charities which are solely concerned with, say, protecting the environment or which are engaged in overseas aid/development.

Charity no worse off

In circumstances where it is not straightforward to identify a causal link between a certain type of investment and a negative social outcome affecting a charity’s beneficiaries, then, provided there is appropriate financial advice that the charity will be no worse off from excluding the investment in question, it is open to the trustees to make a decision based on appropriate ESG considerations.

Similarly, if trustees are presented with two investment choices, both of which deliver equivalent financial outcomes, the trustees may decide based upon ethical or ESG considerations. In this way, it is possible to integrate ESG considerations where they serve as a point of differentiation between equally attractive investment alternatives.

Alienating the charity’s supporters

A further exception is that trustees can have regard to the views of their supporters and beneficiaries when making investment decisions, provided they are satisfied that this would not involve a risk of significant financial detriment. What stakeholders may object to or find morally repugnant obviously evolves over time. Companies which knowingly contribute to climate change may well now be perceived as a sin stock with public opinion steadily hardening towards fossil fuel companies.

Trustees will therefore need to consider to what extent they may accommodate such views on the one hand and operate a sufficiently balanced and diversified portfolio on the other.

Just nice to have?

As things stand, there is no general requirement in law for investment decisions to be made exclusively in a manner which is consistent with ESG considerations.

However, on the basis that ESG considerations better enable trustees to understand underlying financial risks that may be attached to certain investments, or how those investments square with the objects of their charities, or what impact such investments may potentially have on the charity’s reputation or its relationship with stakeholders, it is clear that trustees should not ignore ESG considerations.

This is particularly in light of the growing link between ESG integration and good financial performance. To have no regard to such a matter could easily be regarded as poor risk management. That said, what weight, if any, which should be given to ESG considerations is for the board to determine with the benefit of proper advice, relative to the purposes and shape of the charity in question.

"…it is…incumbent…to understand the positive correlation between financial performance and ESG considerations which, of itself, might justify favouring investments which are less exposed to ESG risks."

"…it is possible to integrate ESG considerations where they serve as a point of differentiation between equally attractive investment alternatives."

Charity investors being better prepared for the future

Scenario analysis, modelling the likely returns of various asset classes under a variety of possible investment scenarios, has become an increasingly important tool in building robust portfolios, aligned to the needs of individual charities. It can help identify real world risks, but also help charities decide on the right asset mix to achieve their long term goals. It is a means to take a more granular approach to investment planning, leaving trustees better prepared for the future.

Just as driving by looking in the rear view mirror is not to be recommended, assuming that investment markets will behave in future as they have done in the past has its limitations. It leaves an investment strategy vulnerable to unexpected events or changes in economic policy. Instead, investment managers need to incorporate a view on likely future events and their impact on financial markets. The financial crisis exposed an over‐reliance on historical statistical relationships with many portfolios found to be poorly diversified when it hit.

More considered approach

Taking a more considered approach to portfolio risk and diversification has become particularly important in recent years, where the impact of extraordinary monetary policy and quantitative easing has distorted returns from financial markets. It means that the future return profiles from various assets are unlikely to be the same as they were in the past. This is particularly true for the bond market. Building scenarios and modelling the likely returns from asset classes under those scenarios can help create more robust, “future proof” portfolios.

Different currency scenarios

This is also important in managing risk and “stress-testing” portfolios. For example, scenario analysis might look at how the portfolio would react to a sudden spike in the oil price. This can help identify if the portfolio is insufficiently diversified, or has a lack of balance. More recently, this has been important in testing portfolios’ sensitivity to various different currency scenarios, notably around Brexit.

It has been used to show the impact of a 25% appreciation and 25% depreciation in sterling on portfolio value. It could also look at how changes in interest rates might impact portfolio income or capital returns.

For charities, scenario analysis can also help identify and meet their specific needs. For example, scenario analysis can help establish a charity’s future cash flow and investment needs to better align its investment strategy. One can look at the likely outcomes given a range of different financial market scenarios to manage risk and ensure that the charity does not run short of cash should markets turn down.

Assessing drawdown exposure

It can also be used to help charities decide between various different scenarios. For example, it can help to visualise the type of drawdown exposures a charity may be exposed to by taking a specific asset allocation/return target. To reach CPI+3% return target in the present interest rate environment one would usually recommend a weighting of around 60% in equities.

Running a scenario analysis for the 2007-2009 global financial crisis on that asset allocation showed that the portfolio would have experienced a maximum drawdown of around 25%. If a charity is uncomfortable with that level of volatility, or wouldn’t be able to meet its commitments, it may be worth looking at a different allocation.

Scenario analysis can also show the impact of different fee rates and market returns on a portfolio’s value. This can help charities look at the “value for money” element of active investing and how they want to balance active and passive investments in their portfolio. It can also help demonstrate what could be achieved by taking additional risk. In this way, scenario analysis can help build a more nuanced and tailored portfolio that works for the individual needs of each charity.

Removing behavioural biases

It can also be important in helping to remove the natural behavioural biases that afflict all investors. One spends a lot of time trying to understand how certain behavioural traits – from an inclination to run with the herd, to “confirmation bias” (where investors interpret evidence to support their prior beliefs) – could affect portfolio returns. This helps eliminate them as far as possible when investing.

Scenarios help with this. If an event, such as a spike in the oil price, has been planned for and a course of action laid out, it prevents “on the hoof” decision-making, which is where investors are particularly vulnerable to behavioural biases. If the course of action has already been laid out, it means decisions are well-considered.

Forward‐looking scenario analysis is a good way to uncover the real risks and upside potential of an investment portfolio, capturing the portfolio’s sensitivity to specific, real world events. It offers a powerful insight into risk, and allows trustees to understand the impact of different market environments and withdrawal profiles on portfolio value.

Scenario analysis in practice

This example shows how scenario analysis can be used by trustees to visualise investment risk and returns in real life terms, providing an important tool to inform strategy discussions. The charity in question was based in the UK and worked in the education sector. The charity had raised a lot of money, but was spending it quickly. The remaining pot was disappearing and the trustees thought one solution may be to move into higher risk assets to grow the pot faster.

A scenario was modelled for the charity to show the problems inherent in taking more risk with the charities’ reserves. This was how it worked:

SCENARIOS. The charity’s portfolio is currently 65% invested in equities, with the balance split equally between UK bonds and alternatives. The primary investment objective is to grow the portfolio ahead of inflation. The charity is budgeting net annual withdrawals of £525,000 (increasing with an inflation rate of 2%). With a current portfolio size of £10m this represents an initial withdrawal rate of 5.25%. A relatively simple scenario analysis was undertaken modelling the portfolio value, taking into account the inflation adjusted withdrawals, under three different market return scenarios, as follows:

BASE SCENARIO. Returns from equities, bonds and alternatives are 7%, 2% and 5% respectively.

BULLISH SCENARIO. Returns from equities, bonds and alternatives are 10%, 2% and 7% respectively.

BEARISH SCENARIO. The first 22 months of returns repeat the 2007-2009 financial crisis, followed by base scenario returns in perpetuity.

RESULTS. The graph below shows the results of the scenario analysis:

Source: including DataStream/Bloomberg as at 31 December 2017.

The annual withdrawals are equal under all three scenarios, but the different market environments lead to dramatically different portfolio values. Under the base case scenario the portfolio maintains its nominal value, but in real terms it does not keep pace with inflation. Under the bullish scenario the portfolio manages to meet the annual withdrawal requirements and grow ahead of inflation.

Greatest insight into risk

But the bearish scenario provides the greatest insight into risk. When the portfolio experiences an initial loss the annual withdrawals become a larger proportion of the total value, and effectively lock in the initial negative returns. Even though the portfolio experiences “base case” returns afterwards the value never recovers from the initial loss, and reaches a £0 value in 2037.

OUTCOME. The scenario analysis suggests that the level of withdrawals is incompatible with the growth ahead of an inflation objective unless the market environment is very supportive. It is reasonable to ask whether the market environment is likely to be supportive after a lengthy bull market in equities, with stock market valuations near long term highs.

It also highlights the impact that withdrawals can have in permanently impairing value in periods of market volatility. The trustees ultimately concluded that an increase in the portfolio’s risk level would not be appropriate given the sensitivity to short term losses, and indeed portfolio risk was actually reduced slightly. A new fundraising strategy was also implemented to increase income and in turn reduce the level of portfolio withdrawals.

Reality of investment risk

THE IMPLICATIONS. Investment managers typically talk about risk in technical terms like standard deviation or tracking error. But these short term metrics fail to capture the day-to-day reality of investment risk for trustees. By using basic scenario analysis one is able to demonstrate how different market environments, risk profiles and withdrawal amounts influence the portfolio’s value and can inform important discussions on the right risk profile for a charity.

Scenario analysis is a potent tool in helping to deliver better, long-term outcomes for charities. It allows for a more granular and detailed understanding of risk and potential rewards, while bringing real world scenarios to bear on the investment strategy. It is a valuable part of the way portfolios are constructed.

"Forward-looking scenario analysis is a good way to uncover the real risks and upside potential of an investment portfolio, capturing the portfolio’s sensitivity to specific, real word events."

"…short term metrics fail to capture the day-to-day reality of investment risk for trustees."

Five ways your investment process can go wrong

Even the best-laid portfolio plans can be derailed by financial market caprices, but charity investors can give themselves a better chance of achieving stable, long term returns by avoiding a number of common mistakes. Here are the top five ways that an investment process often goes wrong.

1. FOCUSING ON THE SHORT TERM AT THE EXPENSE OF THE LONG TERM. When managing portfolios, investors need to consider both strategic and tactical asset allocation. Strategic asset allocation is the long term allocation to bonds, equities and other assets based on an investor’s risk parameters and goals. Tactical asset allocation is shorter term, aiming to adjust for temporary anomalies in markets, either to capitalise from mispricing, or protect portfolio returns against volatility.

Overall risk reward

Strategic asset allocation is similar to climate. Climate shapes the long term trend that sets the overall risk reward situation and changes slowly. For example, is the climate getting hotter (inflationary) or colder (deflationary) which in turn sets the tone for what works best overall in markets?

Tactical asset allocation is similar to the weather forecast. Do we need to take an umbrella when we leave the house tomorrow? Weather changes all the time, it accounts for most of the “noise” in markets and it is what drives 90% of the discussion you hear from market commentators.

It is easy to spend a lot of time talking about the weather (and many fund managers enjoy doing it) – politics in Europe, the latest manufacturing survey, the US/China trade negotiations, the latest employment numbers etc. . However, this can be a distraction from the more important business of establishing the investment climate and when it changes.

2. ASSUMING THE FUTURE WILL BE LIKE THE PAST. Often, investors will use the past behaviour of different asset classes to set their asset allocation today. For example, they may assume that because bonds have performed well at times of declining equity markets, they will continue to do so in the current volatility.

However, interest rate levels are very much lower today, economies and policies change and the past may be very different to the future. This has been particularly true in the wake of the global financial crisis as quantitative easing has distorted all markets.

Investment grade bonds

For example, historic annualised returns on a basket of investment grade bonds have been over 5% but bond yields used to be far higher. It is likely bond returns will be structurally lower going forward and those who expect returns to continue at 5% per year could be disappointed.

If you set your asset allocation and portfolio construction based on historic return and risk expectations, you might well find that your portfolios are not as diversified as expected In building the right asset allocation, you need to build in a sensible estimate of forward returns from various markets and the level of correlation between assets in different environments. While one cannot do this with accuracy, it is far better than assuming tomorrow will be exactly like yesterday.

3. BELIEVING ASSET ALLOCATION IS ALL THAT MATTERS. Does the following sound familiar? “One study suggests that more than 91.5% of a portfolio’s return is attributable to its mix of asset classes. In this study, individual stock selection and market timing accounted for less than 7% of a diversified portfolio’s return.”

Variation in quarterly returns

This is one of the most misquoted statements in the financial world. The original 1980s study by Brinson, Hood and Beehower found that asset allocation accounts for c.90%+ of the variation in a portfolio’s quarterly returns, not the level of returns themselves. This is an important distinction.

That is not to say that getting the asset allocation mix right isn’t important. A 2000 study by Ibbotson and Kaplan found, “40% of the return variation between funds is due to asset allocation”, but it also found that the balance was due to other factors, including asset class timing, style within asset classes, security selection, and fees.

In other words, investors cannot neglect the other elements in a portfolio believing that asset allocation is the only determinant of returns. Investors who do this often tend to populate their portfolios with passive funds, rather than actively selecting their holdings. Passive funds essentially follow a momentum strategy where they strategies buy new stocks when they are expensive and sell them when they are cheap.

One study found that from October 1989 to December 2017, the performance of stocks added to passive portfolios lagged those that were sold by an average of over 22% over the following year. This is the opposite of what famous investors such as Warren Buffet have advocated their whole careers - buying quality stocks at cheap prices.

Stock selection is also a key part of overall investment returns and risk control, one where expertise can add significant value. Some market participants and other investment houses have given up on this part of the process.

4. FALLING PREY TO BEHAVIOURAL BIASES. As humans we make poor investors because thousands of years of evolution mean that we are hard wired to certain behaviours. This is often seen as a problem only for hobbyist investors, who get caught up with fads, such as the technology bubble. There may be some truth in that, but all investors – including professional investors – are vulnerable to these issues no matter how many years of experience they have.

Commonplace behavioural biases

Over 100 behavioural biases have been uncovered, but there are a number that are commonplace: anchoring, for example, is when investors make decisions based on an arbitrary reference point. Gamblers’ fallacy is an assumption of reversion to the mean in circumstances and in series when there is no evidence that it exists.

At the same time, investors may be over-confident. This is particularly applicable to financial market professionals who may be very knowledgeable about a subject area and inclined to neglect information that is contrary to their view.

The phenomenon of “herding” will be familiar. Investors’ inclination to run with the herd, rather than strike out alone, is the key reason that investment “bubbles” form. It feels comfortable to act in the same way as other people, but the herd is not necessarily right, as many investors found out painfully when the technology bubble crashed in 2000.

Investors generally dislike losses (loss aversion) far more than they appreciate the equivalent gains. This can make them act irrationally, by taking much bigger risk to avoid a small loss, even when it would be far outweighed by the potential gain. Recency bias is a tendency to place greater weight on recent events, even when there is no reason for them to hold a higher weight.

What can we do about these behavioural biases? Being aware of this kind of problem is the first step in trying to avoid them. Quantitative models help us to look at markets objectively and ensure we are looking at the same data in the same way every day, month, quarter, year when we review portfolios and make tactical asset allocation decisions.

5. IGNORING PORTFOLIO CONSTRUCTION AND DIVERSIFICATION. It is easy to spend a lot of time focusing on selecting individual assets, without ever looking at how they come together in a portfolio. Portfolio construction is vitally important: markets rarely remain in equilibrium for long and always retain the potential to surprise us. Rising interest rates, geopolitical risk, environmental change and “black swan” events can all derail a portfolio in spite of the most meticulous planning.

Possibly being wrong

While it is clear portfolios should be biased towards what you think is most likely to happen, it is important to consider that we might be wrong. Portfolios include assets that would also do well if the unexpected happens or the initial analysis was incorrect. A common mistake is to think that financial markets will give you time to reposition: they often don’t. The common example given is the narrow door of a cinema on fire.

"…investors cannot neglect the other elements in a portfolio believing that asset allocation is the only determinant of returns."

"Investors generally dislike losses (loss aversion) far more than they appreciate the equivalent gains."

Picking the right benchmark for charity investment performance

As part of their duty of care, charity trustees need to demonstrate effective monitoring of their investments and benchmarks are frequently used as part of this task. They face an array of different benchmarks to choose from. But what exactly is a benchmark and how are they best used?

Benchmarks are used for three main types of purpose. First, they can be used to set constraints on the types of asset and their proportions held in a portfolio. Second, they can be used to set targets to beat and third, they are often used to provide a comparator of similar strategies or client types.

There are three main types of benchmark: composite indices, target return (also known as absolute return) and peer group benchmarks.

A composite benchmark typically combines a series of market indices in similar proportions to the portfolio’s long term strategic asset allocation – assets held can be mapped/matched against long term liabilities to help determine the long term risk/return objectives.

The portfolio might include a mix of fixed interest, equity, alternative and real estate assets. For example, the UK government fixed interest exposure might be measured against the Markit iBoxx All Gilt index, the UK equity exposure against the MSCI UK Equity index, and so on. In turn these can be used to set constraints on the types of assets held - often minimum and maximum ranges are added within which a manager can act with discretion.

Comparison with subcomponents

This type of benchmark is also useful because it allows performance between the portfolio and the benchmark to be directly compared with its subcomponents. This in turn allows analysis of the differences at each level to be broken into asset allocation, stock picking and timing decisions. This can give important information to both the investment manager and client about the drivers of performance.

A target return benchmark measures portfolio progress against a fixed yardstick. For many charities the yardstick is preservation of the portfolio capital in real terms over the long term. A target return benchmark might therefore be an inflation measure (consumer price inflation - CPI, or retail price inflation - RPI) plus a margin to provide for income generation, costs and a buffer – in all this could be 3%-4% or more depending on risk profile and the inflation measure used.

It is important to remember that this is a longer term benchmark, most often used as a target to beat, and is less appropriate over short periods or in providing comparative data. Although not recommended due to distortions in index construction, composite benchmarks can also be used as targets to beat.

Peer group benchmarks were the first type of benchmark to be popularly used, and arose from the desire to compare portfolio performance with those portfolios invested by other managers. This usually involves looking at the performance of a group of charities or other funds which may or may not share similar objectives and risk profiles to your own. This can be a useful sense check to see how your portfolio is performing compared to others.

However, significantly, peer group benchmarks often do not consider the bespoke objectives of a charity and often group together portfolios with very different asset allocations and investment approaches. Thus focusing too much on relative peer group performance can distract from the ultimate objectives of a charity’s investments. As noted, their main use is as a comparative, but composite benchmarks can also be used for this purpose.

Evolution of benchmarks

It is helpful to note how benchmarks have evolved over the past 30 years, and how they can help meet the needs of the latest generations of investment managers and trustees. As already mentioned, peer group benchmarks were the first type of benchmark to become popular. The problem with the early peer group benchmarks was that only return was considered, irrespective of the risk taken to achieve those returns.

Thus trustees of portfolios underperforming the peer group may have been tempted to shift to riskier, better performing managers in order to achieve these higher returns. This realisation often encouraged fund managers to take on more risk in a race to the top of the table. The result of this was that in the inevitable downturn portfolios proved to be riskier than trustees were comfortable with.

Best practice led to the greater use of composite index benchmarks which looked like an ideal solution. However, trustees began to monitor achievement of their longterm objectives on increasingly short time frames, not over the full investment cycles which most active investment styles need.

Unsophisticated and impatient clients tended to buy managers at the peak of their outperformance and then sell out at their trough, thus damaging investment returns. In turn, investment managers learnt that it was safer in terms of mandate retention to tightly (“closet”) track the composite benchmark. Benchmark tracking error became a substitute for real risk.

With less real active management came less outperformance, opening the door for the rise in passive management. More importantly for this discussion, with the bursting of the dot.com bubble in 2000 and the financial crisis of 2008, trustees tended not to be that impressed when told how good performance had been – with, say, portfolios down by “only” 28%, when the benchmark fell by 30%.

This in turn has led to the greater use of the target return benchmark. However, as we go through the tenth year of the recovery after the financial crisis, there are a lot of investors wondering whether they made the right decision to track RPI + 3% during a period when markets have averaged RPI + 9%. In addition, these types of absolute returns can typically only be achieved in a downturn through the use of derivatives to protect from losses.

The cost of maintaining this type of insurance is usually prohibitively expensive, and so there are likely to be many portfolios that struggle to achieve these targets through the end of the cycle, whenever that may be.

Which benchmark is best?

The main problem with choosing benchmarks is that the moment anything is specifically measured, it tends to distort manager behaviour. This is as true of benchmarks to monitor hospital waiting times as it is of portfolio monitoring. In addition, investment managers and their clients often confuse the uses of different benchmarks and the time horizons over which they are most effective. Accordingly it is best to establish the types of benchmark, their use and the effective time horizon at the start of each mandate.

Each of the three types of investment benchmark discussed capture desirable characteristics that trustees would want to encourage and monitor in a portfolio. However, the focus on just one benchmark invariably leads to other desirable portfolio characteristics being neglected. As there is no single solution charities increasingly use a combination of all three types to reflect the uses to which each is best suited.

This approach helps provide a balance of desirable characteristics being monitored and encourages both the trustee and investment manager to pay close attention to all the characteristics. While this approach does not provide a hard and fast test of success and failure in the short term, it does help ensure that everyone is more focused on what really matters through the whole investment cycle.

How to use benchmarks

Charity trustees need to monitor the performance of their fund manager to make sure performance and risk are in line with expectations. However, expecting performance to match the benchmark at all times and in all situations is unrealistic. In order to beat the benchmark investment managers have to take positions away from the benchmark. Indeed, the question arises as to whether paying too much attention to the benchmark risks putting the cart before the horse.

Performance measurement is relatively easy to do but it is not a panacea. Moreover it can distract from the more detailed monitoring that investors frequently carry out when awarding mandates and then often ignore thereafter.

There is also a need to consider appropriate time horizons. For example, one might ask if measuring something over only three years is a misalignment of time horizons with a charity’s long term objectives. Given potential volatility, it is generally preferable that the longer the period a benchmark covers, the better. With any period of less than 10 years, it is hard to statistically distinguish skill from luck.

Some kinds of investments or strategies will work better than others in a bull or a bear market which means trustees should be looking at the whole investment cycle – peak to peak or trough to trough when assessing an investment manager’s performance. It is surprising how often there are requests to supply historic data for only five years by charity trustees or consultants looking to review investment managers.

A measured approach

The optimal solution is likely to depend on what a charity is looking to measure, as well as its sources of funding, its need for returns and its risk appetite, as well as its financial condition, its size and its scope of operations. Nevertheless, most charities with significant invested assets could probably benefit from a variety of benchmarks to ensure they are getting the most comprehensive view of the performance being delivered.

Ultimately, trustees have an obligation both to the charity’s beneficiaries and to the regulator to ensure that due consideration has been given to the ways in which the charity funds itself, including its investments. Benchmarks represent a useful tool in terms of providing some much needed transparency, but these should be used alongside monitoring of the ongoing investment process, portfolio construction, risk mitigation measures and the investment firm’s culture.

"…expecting performance to match the benchmark at all times and in all situations is unrealistic."

"…one might ask if measuring something over only three years is a misalignment of time horizons with a charity’s long term objectives."